By Matt Lefebvre

Please read the introduction to this series before reading this article.

To read along with audio for this article, click here Resurrection-Part 1

Introduction

It is a unique feature of a cumulative case for God’s existence that each individual argument, on its own, does not establish all the traditional attributes of God; in the case of this series, the God of Christianity. While some would consider this a reason to ignore the argument, it is precisely the nature of the cumulative case that allows any given argument to remain limited in its scope, for the individual arguments employed are not intended to give the whole picture alone, but form, as it were, a piece of the puzzle. Hopefully then, the arguments together create a strong case for the existence of God that cannot be ignored. Richard Dawkins illustrates this point well for our purposes, albeit unintentionally. In reference to the cosmological argument for God’s existence, Dawkins counters, “Even if we allow the dubious luxury of arbitrarily conjuring up a terminator to an infinite regress and giving it a name, simply because we need one, there is absolutely no reason to endow that terminator with any of the properties normally ascribed to God: omnipotence, omniscience, goodness, creativity of design, to say nothing of such human attributes as listening to prayers, forgiving sins and reading innermost thoughts.” (The God Delusion, p.101). If you have already read the cosmological argument in this series, or have heard of it before, perhaps you can appreciate the humour in this admission. In fact, William Lane Craig includes this as #10 on his Ten Worst objections to the Kalam Cosmological Argument, and after reading this quote from Dawkins, Craig responds, “So what?” The funny part is that Dawkins does not refute either of the premises, but simply complains of the argument not proving more. Well, that is just the thing…the cosmological argument does not attempt to prove these other things. However, what we do have can be found near the end of my article in this series on the cosmological argument: “So to sum up, we have a transcendent, timeless, nonspatial, immaterial, supremely powerful, supremely intelligent, personal cause.” If we are looking for other attributes, other arguments are useful (Ex. the moral argument is helpful in establishing that God is good), and we need not fault an argument for not establishing more than it intends to.

It is a unique feature of a cumulative case for God’s existence that each individual argument, on its own, does not establish all the traditional attributes of God; in the case of this series, the God of Christianity. While some would consider this a reason to ignore the argument, it is precisely the nature of the cumulative case that allows any given argument to remain limited in its scope, for the individual arguments employed are not intended to give the whole picture alone, but form, as it were, a piece of the puzzle. Hopefully then, the arguments together create a strong case for the existence of God that cannot be ignored. Richard Dawkins illustrates this point well for our purposes, albeit unintentionally. In reference to the cosmological argument for God’s existence, Dawkins counters, “Even if we allow the dubious luxury of arbitrarily conjuring up a terminator to an infinite regress and giving it a name, simply because we need one, there is absolutely no reason to endow that terminator with any of the properties normally ascribed to God: omnipotence, omniscience, goodness, creativity of design, to say nothing of such human attributes as listening to prayers, forgiving sins and reading innermost thoughts.” (The God Delusion, p.101). If you have already read the cosmological argument in this series, or have heard of it before, perhaps you can appreciate the humour in this admission. In fact, William Lane Craig includes this as #10 on his Ten Worst objections to the Kalam Cosmological Argument, and after reading this quote from Dawkins, Craig responds, “So what?” The funny part is that Dawkins does not refute either of the premises, but simply complains of the argument not proving more. Well, that is just the thing…the cosmological argument does not attempt to prove these other things. However, what we do have can be found near the end of my article in this series on the cosmological argument: “So to sum up, we have a transcendent, timeless, nonspatial, immaterial, supremely powerful, supremely intelligent, personal cause.” If we are looking for other attributes, other arguments are useful (Ex. the moral argument is helpful in establishing that God is good), and we need not fault an argument for not establishing more than it intends to.

That being said, sometimes it can seem like arguments for the existence of God are a little general. After all, many could concede that there is some overarching power who created the world, and maybe even that such a being is fundamentally good, but still not be Christians. I certainly agree that this is true, and that the theism so far contended for in the cosmological, teleological, and moral arguments is not exclusively Christian.  However, this is precisely where the argument from Jesus’ resurrection comes in. This just happens to be my favourite argument for God’s existence, not because I think that the other arguments are not strong, but because I find this particular argument to be specific to Christianity. It is all well and good to talk about the existence of a higher power in one form or another in most major religions, or maybe even to talk of a powerful first cause that created the world without intending to be directly involved subsequently. However, as soon as the prospect of evidence for a physical resurrection happening in history within a particular religious tradition enters the equation, the viability of a host of religious views could legitimately be severed, depending on the truth of such evidence, of course. If Jesus is just another religious founder who just lived, taught some things, and died, He would be about on the same level as all the rest, but if it is really true that God raised Him from the dead, this would be an unparalleled event within history. Since no other founder of a major religion has claimed that they would be raised from the dead (Wilbur Smith, in New Evidence That Demands A Verdict, p.209), much less have been able to prove it, if Jesus’ resurrection took place within history, this would place the case for the existence of the Christian (not just generic) God head and shoulders above other religious claims. For those who think I am being overly generous toward my own faith, I will soberly mention that this knife cuts both ways, for if Jesus has not been raised from the dead, my faith is in vain and futile (1 Corinthians 15:14-20).

However, this is precisely where the argument from Jesus’ resurrection comes in. This just happens to be my favourite argument for God’s existence, not because I think that the other arguments are not strong, but because I find this particular argument to be specific to Christianity. It is all well and good to talk about the existence of a higher power in one form or another in most major religions, or maybe even to talk of a powerful first cause that created the world without intending to be directly involved subsequently. However, as soon as the prospect of evidence for a physical resurrection happening in history within a particular religious tradition enters the equation, the viability of a host of religious views could legitimately be severed, depending on the truth of such evidence, of course. If Jesus is just another religious founder who just lived, taught some things, and died, He would be about on the same level as all the rest, but if it is really true that God raised Him from the dead, this would be an unparalleled event within history. Since no other founder of a major religion has claimed that they would be raised from the dead (Wilbur Smith, in New Evidence That Demands A Verdict, p.209), much less have been able to prove it, if Jesus’ resurrection took place within history, this would place the case for the existence of the Christian (not just generic) God head and shoulders above other religious claims. For those who think I am being overly generous toward my own faith, I will soberly mention that this knife cuts both ways, for if Jesus has not been raised from the dead, my faith is in vain and futile (1 Corinthians 15:14-20).

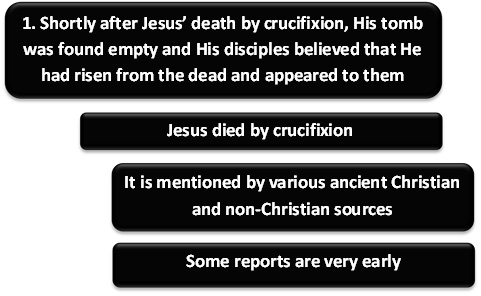

So, all that to point out that the question of Jesus’ resurrection is of enormous significance. How then do we proceed in attempting to answer this question, you might ask? After all, is the resurrection not something to be rejected or accepted based on personal skepticism or Christian faith respectively? Well, as a matter of fact, there are a few points of agreement regarding events surrounding the event in question among scholars who range from conservative Christians to theological liberals, and even to antagonists toward the Christian faith. The reason for the wide agreement on these historical points, which have also been called minimal facts or historical bedrock, is clearly not based on common religious beliefs, but rather on the strength of the historical evidence for these facts. For those engaged in historical Jesus studies, any scheme attempting to explain what happened with Jesus on Easter Sunday must include these widely accepted facts. This is quite significant, because I believe a very strong case for God having raised Jesus from the dead can be made by incorporating these historical facts that are so well-accepted. At the same time, these facts are also sufficient to show the inadequacy of alternate explanations, which serves as an added bonus. I believe that the resurrection hypothesis is strong enough by itself, but the failure of other attempts to explain the facts apart from the resurrection serves to add weight to the scales in favour of Jesus actually being raised from the dead. The form of the argument will be to first explain what these facts are, as well as some of the reasons for their historicity, followed by a look at the implications of these facts for various hypotheses, including the resurrection of Jesus, of course. My contentions are as follows:

The reason for the wide agreement on these historical points, which have also been called minimal facts or historical bedrock, is clearly not based on common religious beliefs, but rather on the strength of the historical evidence for these facts. For those engaged in historical Jesus studies, any scheme attempting to explain what happened with Jesus on Easter Sunday must include these widely accepted facts. This is quite significant, because I believe a very strong case for God having raised Jesus from the dead can be made by incorporating these historical facts that are so well-accepted. At the same time, these facts are also sufficient to show the inadequacy of alternate explanations, which serves as an added bonus. I believe that the resurrection hypothesis is strong enough by itself, but the failure of other attempts to explain the facts apart from the resurrection serves to add weight to the scales in favour of Jesus actually being raised from the dead. The form of the argument will be to first explain what these facts are, as well as some of the reasons for their historicity, followed by a look at the implications of these facts for various hypotheses, including the resurrection of Jesus, of course. My contentions are as follows:

- Shortly after Jesus’ death by crucifixion, His tomb was found empty and His disciples believed that He had risen from the dead and appeared to them

- Belief in these phenomena led to the rapid spread of the Christian faith

- The best explanation of these phenomena is that God raised Jesus from the dead

My hope is that the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus will lead to acceptance, not just of the existence of some distant God off somewhere, but of the existence of a God integrally involved in His creation; a God who raises the dead.

1. Shortly after Jesus’ death by crucifixion, His tomb was found empty and His disciples believed that He had risen from the dead and appeared to them

Have you ever heard someone claim something like, “Most people believe…” or “The majority of experts agree…” or “Nine out of ten dentists confirm…”? Have you ever felt like asking them where they got those generalizations from? A fair question when presented with an apparent consensus could be to ask whether such a statement is based on a critical survey or if it is in fact just an educated guess (or even just an ordinary guess).  In the present case, however, when I mention that there are a few widely accepted facts, this is based on the pain-staking and extensive research of historical Jesus scholar Gary Habermas. In 2005, he published a summary of historical Jesus studies based on 3,400 sources going back to 1975 in French, German, and English in the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus entitled “Resurrection Research from 1975 to the Present: What are Critical Scholars Saying?” (p.135-153). How do we know that there is widespread agreement among scholars concerning these historical facts surrounding what happened to Jesus? We can know this, because, thankfully, Habermas has largely consulted them. So when we speak of these minimal facts, we can be confident that the experts have confirmed these. However, we do not just believe them because scholars affirm their historicity, because sometimes scholars can be quite off on a particular topic, but also because these facts are strongly evidenced. It is not just that scholars like these particular facts, and it can even be mentioned that many do not like having to explain them, but scholars accept these facts because there are good historical reasons for doing so. For some people, it might be enough to just take the word of those who know, or at least claim to know, what they are talking about, but it is important to realize that it is not always “the facts” that determine what scholars think about the past. To one degree or another, a scholar’s presuppositions play a role in what they accept or reject. In fact, many would attest to the fact that “Philosophical presuppositions and historical evidence are not always good friends.” (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.100). Thus, in affirming these facts, I will also include various reasons for accepting them, so hopefully it can also be clear to you why these can be used to support the resurrection as the best explanation. To state the facts more formerly in order: Jesus died by crucifixion-Jesus’ tomb was found empty-Jesus’ disciples believed that He had risen from the dead and appeared to them. Connected with this is the origin of the Christian faith, and along with that, the conversion of Paul, which will be discussed in the second section. In discussing these facts, I will limit myself to one objection per fact, for the sake of space, but various alternate explanations of the resurrection as a whole have been addressed in my article Following the Evidence Wherever It Leads based on the Minimal Facts Approach.

In the present case, however, when I mention that there are a few widely accepted facts, this is based on the pain-staking and extensive research of historical Jesus scholar Gary Habermas. In 2005, he published a summary of historical Jesus studies based on 3,400 sources going back to 1975 in French, German, and English in the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus entitled “Resurrection Research from 1975 to the Present: What are Critical Scholars Saying?” (p.135-153). How do we know that there is widespread agreement among scholars concerning these historical facts surrounding what happened to Jesus? We can know this, because, thankfully, Habermas has largely consulted them. So when we speak of these minimal facts, we can be confident that the experts have confirmed these. However, we do not just believe them because scholars affirm their historicity, because sometimes scholars can be quite off on a particular topic, but also because these facts are strongly evidenced. It is not just that scholars like these particular facts, and it can even be mentioned that many do not like having to explain them, but scholars accept these facts because there are good historical reasons for doing so. For some people, it might be enough to just take the word of those who know, or at least claim to know, what they are talking about, but it is important to realize that it is not always “the facts” that determine what scholars think about the past. To one degree or another, a scholar’s presuppositions play a role in what they accept or reject. In fact, many would attest to the fact that “Philosophical presuppositions and historical evidence are not always good friends.” (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.100). Thus, in affirming these facts, I will also include various reasons for accepting them, so hopefully it can also be clear to you why these can be used to support the resurrection as the best explanation. To state the facts more formerly in order: Jesus died by crucifixion-Jesus’ tomb was found empty-Jesus’ disciples believed that He had risen from the dead and appeared to them. Connected with this is the origin of the Christian faith, and along with that, the conversion of Paul, which will be discussed in the second section. In discussing these facts, I will limit myself to one objection per fact, for the sake of space, but various alternate explanations of the resurrection as a whole have been addressed in my article Following the Evidence Wherever It Leads based on the Minimal Facts Approach.

Jesus died by crucifixion

There is a very important prerequisite for a resurrection of a dead body; namely, it has to be dead first. This may seem simple and uncontroversial, but there have been some attempts to explain the resurrection by suggesting that Jesus was not actually dead in the first place. Although Jesus’ death by crucifixion is one of the historical facts widely accepted, the idea that Jesus was not really dead has been put forward in the past and still rears its head from time to time outside the scholarly community.  As the story goes, Jesus was thought to be dead and was taken down from the cross, before succumbing to death. There is also the suggestion that Jesus was not actually crucified, as in Islam (Sura 4:157-158). However, since this is not based on any early testimony that might contain accurate historical information and goes against what is known from early testimony, I will not pay this objection any more attention. However, the contention that Jesus did not die, though not necessarily taking everything written in the Gospels as fact, seems to have initial support from within the report of Mark. In 15:44 Mark writes, “Pilate was surprised to hear that he should have already died. And summoning the centurion, he asked him whether he was already dead.” With the possibility of Jesus being taken down early from the cross, the scenario goes something along these lines:

As the story goes, Jesus was thought to be dead and was taken down from the cross, before succumbing to death. There is also the suggestion that Jesus was not actually crucified, as in Islam (Sura 4:157-158). However, since this is not based on any early testimony that might contain accurate historical information and goes against what is known from early testimony, I will not pay this objection any more attention. However, the contention that Jesus did not die, though not necessarily taking everything written in the Gospels as fact, seems to have initial support from within the report of Mark. In 15:44 Mark writes, “Pilate was surprised to hear that he should have already died. And summoning the centurion, he asked him whether he was already dead.” With the possibility of Jesus being taken down early from the cross, the scenario goes something along these lines:

Jesus did not die on the cross, but just fainted, and was thus mistaken for being dead. Having been taken down, he was laid in a tomb, and in the coolness of the tomb, he woke up. Upon returning to His disciples, they believed that He had been raised from the dead (Frank Morison, Who Moved the Stone?, p.104-105).

Could that have been what really happened? Well, there are at least four good reasons for accepting that Jesus did actually die on the cross. Before going on to these, though, it is worth mentioning that this idea suffered a scathing critique by a scholar who did not believe Jesus was resurrected, but nonetheless, considered the proposition that he did not die thoroughly implausible. Liberal theologian David Strauss pointed out a series of obstacles that the crucified Jesus would need to overcome. Even if He could survive crucifixion, how would he remove the stone of the tomb, considering His condition, the weight and incline of the stone, and the lack of an edge on which to push from the inside? Even if He could get out, how would He walk the distance to where the disciples were hiding on His wounded feet? Even if He could make it to His disciples, how would they think He was the resurrected and glorified Prince of life in His sad physical shape (A New Life of Jesus, p.408-412)?  To this could be added that there was a guard both at the crucifixion and at the tomb which would be responsible for guarding the body of the victim and corpse respectively. They could even be executed for failing this duty (Craig Keener, Bible Background Commentary NT, p.130). So not only does Jesus have to be taken down from the cross alive with the guard responsible there, but He also has to get past them to get to His disciples. If I were to add evidence against this particular objection, I would rightly be accused of beating a dead horse, but in the interest of also ruling out other doubts about Jesus having really died, I turn now to the positive support for the death of Jesus by crucifixion.

To this could be added that there was a guard both at the crucifixion and at the tomb which would be responsible for guarding the body of the victim and corpse respectively. They could even be executed for failing this duty (Craig Keener, Bible Background Commentary NT, p.130). So not only does Jesus have to be taken down from the cross alive with the guard responsible there, but He also has to get past them to get to His disciples. If I were to add evidence against this particular objection, I would rightly be accused of beating a dead horse, but in the interest of also ruling out other doubts about Jesus having really died, I turn now to the positive support for the death of Jesus by crucifixion.

1. Jesus’ death by crucifixion is attested by various ancient sources, Christian and non-Christian alike.  The Christian literature includes the canonical literature (the four Gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters, 1 Peter, and Revelation) and extrabibilical Christian literature (Ignatius’ letters, the Epistle of Barnabas, and many Gnostic sources). However, it is not just from the Christians, but also Jewish and secular Roman testimony exists (Josephus, Tacitus, Lucian, Mara bar Serapion, and the Talmud). In addition, there is no ancient evidence to the contrary (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.187-189, 192-196, 202-204, 206-208; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.304-305).

The Christian literature includes the canonical literature (the four Gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters, 1 Peter, and Revelation) and extrabibilical Christian literature (Ignatius’ letters, the Epistle of Barnabas, and many Gnostic sources). However, it is not just from the Christians, but also Jewish and secular Roman testimony exists (Josephus, Tacitus, Lucian, Mara bar Serapion, and the Talmud). In addition, there is no ancient evidence to the contrary (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.187-189, 192-196, 202-204, 206-208; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.304-305).

2. Not only are there many reports, but there are also some reports that are very early. Paul mentions Jesus’ death by crucifixion no later than 55AD (1 Corinthians 15:3-8, Galatians 3:1), but even this was already preached to the Corinthians around 51AD when he founded the church in Corinth and to the Galatians even earlier. But wait, it gets better! Scholars have identified oral tradition behind what Paul delivers in 1 Corinthians 15, and in fact, the words Paul uses for “delivered” and “received” (ESV) are words often used for passing on formal tradition. There is widespread agreement that Paul received this from the Jerusalem apostles and that it was within 3 to 8 years of Jesus crucifixion! This is indeed very early, but since this is only when Paul receives the tradition, it must have been formulated even earlier (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.152-157; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.223-235, 305-306).

3. There is also internal evidence for belief in Gospel narratives of Jesus’ crucifixion themselves. First of all, being crucified was a shameful thing, but especially for someone like Jesus.

Second, there was no belief that the Messiah would be crucified and this goes against the common Jewish picture of the Messiah.

Third, Jesus is depicted as a martyr who is struggling through His martyrdom, when a number of other accounts of Jewish martyrs show bravery in the face of torture and death. The account of Jesus’ crucifixion would be hard to explain as pure fiction.

Fourth, the Gospels include incidental details that coincide with what we know of crucifixion from other sources. These include crowds following Jesus to Golgotha, the breaking of the criminals’ legs, the piercing of Jesus’ side with a spear, and the Jews desiring to take the bodies down before sunset, prior to the Sabbath. These details attest to the historicity of the passion narratives (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.73-75; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.306-311).

Fourth, the Gospels include incidental details that coincide with what we know of crucifixion from other sources. These include crowds following Jesus to Golgotha, the breaking of the criminals’ legs, the piercing of Jesus’ side with a spear, and the Jews desiring to take the bodies down before sunset, prior to the Sabbath. These details attest to the historicity of the passion narratives (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.73-75; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.306-311).

4. As unlikely as the objection above seems, as pointed out by Strauss, it is even more unlikely considering how improbable it is that someone would survive crucifixion. First, the torture that often preceded crucifixion was very brutal, which would already weaken the victim.

Second, there is only one ancient report of someone surviving crucifixion, given to us by Josephus, but even though three of Josephus’ friends were taken down from their crosses and given the best care Rome had to offer, two out of the three still died.

Third, death by crucifixion is believed to be due to asphyxiation (not being able to exhale), so crucified criminals would have to push up using their nailed feet to breathe out. This would not only make it easy to see if someone was dead, because most people would not survive more than ten or twelve minutes in the hanging position without lifting up, but it would also explain why breaking the legs of the criminals would speed up the process, as in the case of the approaching Sabbath when Jesus was crucified.

Fourth, an article that appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association concerning the methods of scourging and crucifixion concluded that “interpretations based on the assumption that Jesus did not die on the cross appear to be at odds with modern medical knowledge.” One of the issues involved the spear thrust into the heart of a crucifixion victim. Romans ensured death by stabbing the heart and the testimony of John 19:34-35 coincides with this modern medical knowledge. The blood and water that John saw would be from the right side of the heart and the pericardium (the sac that surrounds the heart) respectively. Even if Jesus were to be alive for a significant amount of time in the hanging position without moving, the spear thrust to the heart would certainly have killed Him (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.73-75; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.304, 311-313).

Fourth, an article that appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association concerning the methods of scourging and crucifixion concluded that “interpretations based on the assumption that Jesus did not die on the cross appear to be at odds with modern medical knowledge.” One of the issues involved the spear thrust into the heart of a crucifixion victim. Romans ensured death by stabbing the heart and the testimony of John 19:34-35 coincides with this modern medical knowledge. The blood and water that John saw would be from the right side of the heart and the pericardium (the sac that surrounds the heart) respectively. Even if Jesus were to be alive for a significant amount of time in the hanging position without moving, the spear thrust to the heart would certainly have killed Him (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.73-75; Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, p.304, 311-313).

The evidence for Jesus’ death by crucifixion is very strong and it is no wonder that so many scholars accept it as fact. Mike Licona (The Resurrection of Jesus, p.313-314) records the statements of two very skeptical scholars, Gerd Lüdemann and John Dominic Crossan, that adequately sum up the view of the scholarly community concerning the death of Jesus:

“Jesus’ death as a consequence of crucifixion is indisputable.” (Lüdemann)

“That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be.” (Crossan)

Click here to see part 2 of the article