by Matt Lefebvre

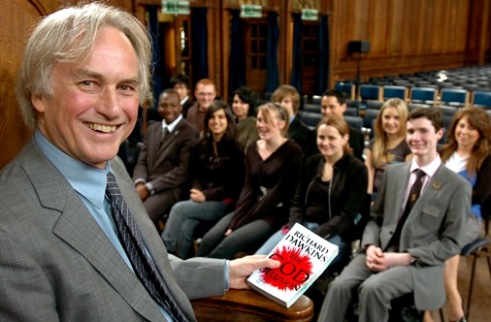

Richard Dawkins with The God Delusion

…is a phrase employed by Richard Dawkins in his book, The God Delusion. He borrows the idea from his appreciation of what feminism did in that area, raising his consciousness about the power of consciousness-raising, and applies it to natural selection, as can be seen on page 141 where he states, “Feminism shows us the power of consciousness-raising, and I want to borrow the technique for natural selection.” He goes on in the same paragraph to say that natural selection explains the whole of life and even raises consciousness concerning the power of science to explain organized complexity coming from simple beginnings without deliberate guidance. Dawkins’ case is to raise consciousness in a number of ways ranging from how people should not be ashamed of being atheists to how the world would be a better place without religion. These areas of discussion make it clear that Dawkins is out to liberate people from the jaws of religion through rationalism and naturalism, but has he, perhaps inadvertently, raised questions that would indeed raise consciousness, but on the side in favour of the existence of God?

This is certainly not Dawkins’ intent and in the preface to the paperback edition he wishes to absolutely distinguish himself from fundamentalists, as he gives this definition, “Fundamentalists know what they believe and they know that nothing will change their minds.” So in as much as Dawkins generalizes faith as blind trust in the absence of evidence, and even in the teeth of evidence, I would hope that he would applaud Christians engaging with the questions he raises in an honest attempt to seek the truth that ultimately shapes the lives we live. Considering that Dawkins does not seem to think there is any evidence for Christian belief, I can’t put words in his mouth, but if he remains consistent to his assertions of following the evidence wherever it leads, I cannot see how he would be opposed to rational arguments, even if they were in support of God’s existence.

However, in order to explore questions such as those raised by Dawkins, it is important to understand what those questions are. The skeptic surprisingly plays a vital role in confirming belief for those willing to engage with the questions, for if a belief is held, it is less common for someone to spend all their time thinking about possible difficulties than for that same person to enjoy the benefits of the positive attributes of the belief, which is likely what attracted them in the first place. Now for some who believe in God, a title like The God Delusion would not naturally put the book on the Christmas wish list, but contrary to popular understanding, knowledge of opposing views can be a first step in confirming your own view and even being able to coherently explain it to those who ask. Paul is a great example of someone who knew his audience to the point of being able to effectively communicate the truth of Christ to pagans, Greek philosophers, magicians, Jews, and whoever might cross his path. If we truly believe something to be true, we should not be afraid of questions asked of this belief, but rather be encouraged with what we do know and challenged to pursue the answers that remain elusive.

Considering that The God Delusion is over 400 pages, the best I will offer here is to simply try to summarize Dawkins’ ideas in the book. In my copy  there is a preface to the paperback edition addressing various criticisms followed by a preface outlining motivations and intentions in the book which are fascinating in themselves, but since those ideas are expanded in the rest of the book, I will jump to the first chapter. The title, A Deeply Religious Non-Believer, is taken from a quote of Albert Einstein and Dawkins devotes space to explaining what Einstein meant. Other quotes from Einstein are employed to convey that the idea of a personal God was foreign to him and that the sense in which Einstein used the word religion was to refer to his awe at the structure of the world. From this, Dawkins says that his title, The God Delusion, is concerned only with supernatural gods and that the respect for the belief in God in this sense is undeserved. He proceeds to offer examples in which religious beliefs are protected from offense and even further, given special consideration and advantage over other ideas or positions that have no religious affiliation. A comparison is made particularly regarding the situation a few years ago involving cartoons of the prophet Muhammad published in Denmark which led to outrage and violence. The connection is then transferred to political cartoons, which are disrespectful to politicians, and yet lack rioting in opposition of such slander. Dawkins states that he is not in favour of offending just for the sake of offending, but also that he will not tip-toe around religion and not handle it as he would anything else.

there is a preface to the paperback edition addressing various criticisms followed by a preface outlining motivations and intentions in the book which are fascinating in themselves, but since those ideas are expanded in the rest of the book, I will jump to the first chapter. The title, A Deeply Religious Non-Believer, is taken from a quote of Albert Einstein and Dawkins devotes space to explaining what Einstein meant. Other quotes from Einstein are employed to convey that the idea of a personal God was foreign to him and that the sense in which Einstein used the word religion was to refer to his awe at the structure of the world. From this, Dawkins says that his title, The God Delusion, is concerned only with supernatural gods and that the respect for the belief in God in this sense is undeserved. He proceeds to offer examples in which religious beliefs are protected from offense and even further, given special consideration and advantage over other ideas or positions that have no religious affiliation. A comparison is made particularly regarding the situation a few years ago involving cartoons of the prophet Muhammad published in Denmark which led to outrage and violence. The connection is then transferred to political cartoons, which are disrespectful to politicians, and yet lack rioting in opposition of such slander. Dawkins states that he is not in favour of offending just for the sake of offending, but also that he will not tip-toe around religion and not handle it as he would anything else.

With that in mind, he turns to the next chapter, The God Hypothesis, in which he looks first at polytheism and then monotheism, stating that they developed in that order. Beside the point, Dawkins sees little difference between the two anyway, or at least, he shows little interest. His arguments in the book go on to refer to God in a general sense, including both polytheistic and monotheistic beliefs in a broad sweep. To Dawkins, the question of which God he is talking about is irrelevant in a book arguing against belief in any supernatural being from the God of the Old Testament to any number of particular Hindu gods. Dawkins has mostly Christianity in mind, but he says it is only because he is most familiar with that one. Dawkins sees Judaism as originally a tribal cult and Christianity as a less monotheistic and less exclusive sect of that. Adding Islam as a later military upgrade, he mentions how Christianity was also spread by the sword. With little interest in discussing what he believes to be more like ethical systems or philosophies of life, like Buddhism, he will not be concerned with other religions. What is of interest to Dawkins, or at least of more interest, is the deism of people such as Voltaire, believing that there is a cosmic Creator, but that He has no personal qualities and is unconcerned with human affairs. These beliefs are extended in the discussion of the founding fathers of America, but Dawkins also contends that deists in earlier times would be atheists in ours. Especially in the case of Thomas Jefferson, whose various quotations include this statement on page 63, “To talk of immaterial existences is to talk of nothings.” This goes with the argument that the greatest of the founding fathers may have been atheists, which is an argument that will be used by Dawkins in other contexts later. Moving on to agnosticism, which is a fancy way of saying you don’t know, he displays how empty he finds this position to be. He uses an illustration from Bertrand Russell in response to calls on the skeptic to disprove belief in God, with the inability to do so being a proof of God’s existence. He suggested that if he said there was a teapot between Earth and Mars orbiting the sun and that it was too small to be seen by the most powerful telescopes, it couldn’t be disproved, and if he said that this fact made it true, he would be thought to be talking nonsense. The point is then made that religion does the same thing with that which is affirmed in ancient books. Similar entities used by Dawkins include the flying spaghetti monster or fairies, but the point is the same: not being able to prove non-existence doesn’t prove that something exists. This leads into a discussion of the separation between science and religion in what they can answer, which Dawkins can’t understand, saying that science has all the answers and religion adds nothing. After discussing the great prayer experiment, in which there was a test of whether prayer would make a difference for sick people, results were negative on the side of prayer helping people. Dawkins concedes that some Christians spoke against it, but he thinks they would think differently if the results had been positive to prayer. Turning from his portrayal of Christianity as a teapot-type assertion, based on inability to disprove it, he moves to finish his chapter with a discussion of what he finds more plausible. On page 94, he suggests, “Suppose Bertrand Russell’s parable had concerned not a teapot in outer space but life in outer space” where the only rational stance for this is agnosticism. However, the concept of extra-terrestrial life is differentiated from gods because of the simplicity of what Dawkins calls Little Green Men, because as he says on page 98, “Entities that are complex enough to be intelligent are products of an evolutionary process.” The idea is that gods required more explanation than they provide and are rendered redundant in light of natural selection.

Chapter 3 deals with arguments for God’s existence and the first contestant is Thomas Aquinas. The first arguments dealt with are Aquinas’ assertions of invoking God to avoid an infinite regress, saying that everything has a cause, so for the universe to exist, there must be a first cause, called God. Dawkins thinks this unhelpful at best and misleading at worst. He states that some regresses reach a natural terminator and that it is not clear that God provides the terminator in the case of the universe. Moving on, humans can be both bad and good, so goodness cannot rest in humans and can only be compared with a maximum, so God is the standard and maximum. Dawkins doesn’t consider this an argument at all. Moving on to the teleological, things in the world appear to be designed and God would be that Designer. Dawkins refers to Charles Darwin’s criticism of the argument from design in William Paley’s Natural Theology and says that evolution by natural selection can seem like design. Another argument addressed is the argument from experience, which Dawkins places in brackets and proceeds to attribute to explanations from hallucinations to psychological problems to being honestly mistaken. Being honestly mistaken spreads into the next argument, the argument from Scripture, for to the argument that Jesus was “Lunatic, Liar or Lord” is added that he might have been honestly mistaken. Dawkins then implies that Scripture sounds good to those not used to asking questions of it and that there is a huge uncertainty surrounding the New Testament. Examples are given of contradictions in the Gospels and the suggestion is made that the four Gospels in the Bible were chosen arbitrarily and are of no more value than other Gospels not included in the Bible. Moving on to religious scientists, Dawkins takes Bertrand Russell’s position that most intellectuals disbelieve the Christian religion, but conceal the fact in public for fear of losing their incomes. In addition, Dawkins implies that those who are religious are only religious in the way Einstein was. Pascal’s Wager and the Bayesian arguments are dealt with last, but as with the rest of the chapter, they are not really treated with any credibility as arguments. At the end of the chapter, Dawkins transitions into what he describes as his central argument, to which he has already alluded several times, summarized by the question, “who made God?”.

In his central argument, titled Why There Almost Certainly Is No God, Dawkins obviously wants to be understood, so he offers his own summary at the end of the chapter. Since this article is only putting forth Dawkins ideas and in no way wanting to misquote him, I will simply use his points in the book.

One of the greatest challenges to the human intellect, over the centuries, has been to explain how the complex, improbable appearance of design in the universe arises.

The natural temptation is to attribute the appearance of design to actual design itself. In the case of a man-made artefact such as a watch, the designer really was an intelligent engineer. It is tempting to apply the same logic to an eye or a wing, a spider or a person.

The temptation is a false one, because the designer hypothesis immediately raises the larger problem of who designed the designer. The whole problem we started out with was the problem of explaining statistical improbability. It is obviously no solution to postulate something even more improbable. We need a “crane” not a “skyhook,” for only a crane can do the business of working up gradually and plausibly from simplicity to otherwise improbable complexity.

The most ingenious and powerful crane so far discovered is Darwinian evolution by natural selection. Darwin and his successors have shown how

Charles Darwin

living creatures, with their spectacular statistical improbability and appearance of design, have evolved by slow, gradual degrees from simple beginnings. We can now safely say that the illusion of design in living creatures is just that – an illusion.

We don’t yet have an equivalent crane for physics. Some kind of multiverse theory could in principle do for physics the same explanatory work as Darwinism does for biology. This kind of explanation is superficially less satisfying than the biological version of Darwinism, because it makes heavier demands on luck. But the anthropic principle entitles us to postulate far more luck than our limited human intuition is comfortable with.

We should not give up hope of a better crane arising in physics, something as powerful as Darwinism is for biology. But even in the absence of a strongly satisfying crane to match the biological one, the relatively weak cranes we have at present are, when abetted by the anthropic principle, self-evidently better than the self-defeating skyhook hypothesis of an intelligent designer.

The explanation of a crane versus a sky-hook is saying that believing in God is throwing a hope up into the sky, expecting God to be an explanation. What I would describe as his main argument against the existence of God is that, since the universe is complex and came about through evolution by natural selection and is in fact improbable, explaining this by God as the Creator would have to make God even more complex, more improbable, and unhelpful, because it would require an explanation for where God came from, leading to an infinite regress. Therefore, though maintaining that disproving God is not possible, Dawkins presents that this argument brings the question of God not existing to almost certainty, making it extremely improbable. Having established that, he turns in the next 4 chapters to where religion comes from, where morality comes from, and what the problem with religion is. The reason being that if God does not exist why do so many people believe in it, why are people good, and what’s the harm of having religion?

For Dawkins, everything must have a Darwinian explanation and religion is no exception. In natural selection, in order for something to be passed on to the next generation, it must have some benefit, but Dawkins quickly qualifies that “benefit” may be misleading, perhaps for fear that religion would be perceived beneficial. He suggests the idea of group selection and that the “benefit” would be either of the group or the idea itself, leading to it being passed on. In addition, Dawkins believes that the survival of religion could be due to a by-product of something else beneficial. Some benefit of safety in groups or listening to parents may be what has made religion survive as cultural norm or just what the parents said, or a combination of various benefit by-products. In a later chapter, Dawkins will return to the idea of parents teaching religion to children and his absolute distaste for it, but in what follows is a heading Tread Softly Because You Tread On My Memes. The title is an obvious allusion to the poetic line “Tread softly because you tread on my dreams” by Yeats, but what are memes? Dawkins provides some explanation. A more familiar term is the term gene, which is a replicator, and natural selection is reliant on replicators, pieces of information that make exact copies of themselves and sometimes inexact copies, otherwise known as mutations. Other examples given by Dawkins are computer viruses and the unfamiliar term meme. Now while genes affect the chances of survival in natural selection, Dawkins suggests that memes could do the same in the case of religion. He mentions the resistance to memes, in that no one knows what memes are made up of, whereas the exact physical nature of a gene is known, consisting of DNA. Another name for memes given by others is cultural variants, or in other words, some things are imitated and passed on to subsequent generations. Why? They are passed on because they work and seem to be successful. The suggestion is that religious memes survive because they go well with other memes that already exist and not necessarily because of intrinsic benefit. These religious memes contribute to survival because they continue in the same cultural norm that is already there in the meme pool. In conclusion of the chapter, Dawkins turns to cargo cults. He gives an example of white people going to islanders and being deified due to the magical nature of the advanced technology of the white men. One in particular was the cult of John Frum, which treated him as a messianic figure with a prophesied return. Accounts of him varied and there is doubt as to whether he ever existed or not, but in any case, the cult developed in new directions, looking to the second coming of John Frum and in other cases claiming to have seen him many times. The connection is then made that Christianity and other religions would have developed in similar ways, starting with a figure, being embellished, and the cults alive today are simply the ones that survived while others passed away. Development along the passage of time would again be due to memes or cultural variants. According to Dawkins, religion is explainable through natural selection and in the next chapter, he turns the same light on morality to explore the roots of that.

Chapter 6 begins with various letters Dawkins has received from nasty Christians that display less than moral attitudes in regard to him. It seems as though his intention is to introduce the idea that Christianity doesn’t produce morality, and to a lesser extent, God shouldn’t need to be defended so ferociously. A phrase that Dawkins put into the mouths of Christians and those sympathetic to Christianity or belief in general goes something like this, “How can one be good without God, or even want to be good?” and he attempts to answer that, true to form, in a Darwinian manner. Much of Dawkins’ attention will be turned to altruisms (or in other words on page 247 “You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours”) and misfiring, mistakes, or by-products, which he has mentioned in the last chapter to refer to religion. Altruisms essentially embody the benefits of being generous, in how kin is treated, in how repayment of favours is expected, in how generosity carries with it a good reputation, and in how generosity gives a partial benefit in giving a perceived authenticity. So what seems selfless may in fact have selfish benefits. As far as the misfiring goes, one example given is sexual desire. Though the benefit for survival would be procreation, the urge or desire is independent of the Darwinian pressure that drove it. Even in these modern times, sexual desire is present even when the possibility of procreation is absent, due to birth control or even infertility. Continuing on with a case study, Dawkins presents a moral dilemma in which a person must choose to make a decision to save five people at the cost of one being killed. He also presents 2 more dilemmas, but the results are the same in that at least 90% made the same moral decision. The inference was that if people get their morality from religion, atheists should differ from religious people in their moral decisions, but the research apparently showed no difference. At this, Dawkins closes the chapter with a question he has been asked by religious people, “If there is no God, why be good?” It is accompanied by a quote from Einstein, “If people are good only because they fear punishment, and hope for reward, then we are a sorry lot indeed.” The point is that morality that is only strong in the presence of policing is not much of a morality. Evidence is also presented concerning the United States that the states that tend to contain more conservative Christians, based on the party that they usually vote for being in power, have more crime, so they do not seem to have the expected increased societal health. The point then made at the end of this chapter refers to absolutism and how, though not always derived from religion, is usually hard to defend apart from religious grounds. Religious absolute morality is usually derived from a holy book, but Dawkins attempts to show in the next chapter this morality is not taken into practiced and that this is a good thing, as Dawkins thinks the religious people should agree upon reflection.

The title of chapter 7, “The “Good” Book and the changing moral Zeitgeist”, sums up, as a good title usually does, Dawkins’ view on morality. There are two main points presented in the chapter: that the good book is not as good as people say, hence the quotation marks in the title, and the Zeitgeist, spirit of the times, changes and morality with it. Beginning with the first point, he takes a few examples from the Old Testament of the Bible, Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19, as well as Jephthah in Judges 11. In Sodom, towns are wiped out because of a desire to “know”, or in other words have sex with, the angels that come to stay at Lot’s. Jephthah makes an oath to sacrifice to the LORD whatever comes out of his gate first and it turns out to be his daughter. There are other examples, interspersed with the idea that the book of Genesis is not to be taken literally anymore, used to illustrate that either the practices are immoral, the role models are not good ones, or that taking it to be non-literal serves no purpose for some kind of didactic fiction, either because the morals are often bad. The point is taken further to illustrate that the theist picks and chooses through the Bible by personal decision the way that the atheist does in choosing moral precepts without an absolute foundation. The claim goes as a quote from page 269 tells, “Those who wish to base their morality literally on the Bible have either not read it or not understood it” and the work of very liberal bishop, John Shelby Spong, is mentioned which is entitled The Sins of Scripture. Dawkins concedes that most religious leaders today do not command the things commanded in the Old Testament, but as he describes, that establishes his point, for the morals are not taken from the Bible and religion does not give a morality unavailable to atheists. From this, Dawkins does not feel it is his responsibility to explain where morality comes from, but to simply say that it does not come from the Bible and that it does depend on the changing moral Zeitgeist. Before doing this, however, there is a description of the New Testament that elevates the teaching of Jesus when compared with the Old Testament in terms of morality, but condemns the doctrine of atonement from sin, by both necessity and decency. According to Dawkins, on page 287 “If God wanted to forgive our sins, why not just forgive them, without having himself tortured and executed in payment – thereby, incidentally, condemning remote future generations of Jews to pogroms and persecution as “Christ-killers”. Not stopping there, he turns to “Love thy neighbor” and interprets it as originally meaning “Love another Jew” which comes to the topic of religious prejudice, including the horror of labeling children with the beliefs of their parents, to which Dawkins will return in chapter 9. Finishing up chapter 7, however, is a description through various examples of how what is acceptable changes over time. A few quotes demonstrate that what was progressive 150 years ago would be considered racist today. The noticeable evil of Hitler’s reign of terror is attributed to his 20th century technology and not to his noticeable difference from men like Caligula or Genghis Khan. A couple pages after the suggestion that Hitler would not have stood out in a time such as theirs, Dawkins returns in the close of the chapter to Hitler and throws Stalin in. He is often confronted with the argument that they were atheists and they did evil things. For Stalin, it is immediately conceded that he was an atheist, and Hitler’s beliefs are discussed at length, with evidence being present for both Christian and anti-Christian standpoints, but above all, the point is made that they did not do their evil because they were atheists, thus making the fact that they were, even if Hitler was, irrelevant. On the contrary, what leads into the next chapter is the fact that religious beliefs are quite the opposite; namely, a cause that makes people do much evil in its name.

In chapter 8, Dawkins deals with what is wrong with religion, not because he says he does not thrive on confrontation, but because of the inherent evil he sees in religion. His hostility, as he puts it, is limited to words and unlike those who would kill in the name of religion. As before, Dawkins vehemently distinguishes himself from fundamentalists. A way that he defines it can be found on page 319, “Fundamentalists know they are right because they have read the truth in a holy book and they know, in advance, that nothing will budge them from their belief.” He follows science, because it is based on evidence, and though he says it is easy to confuse fundamentalism with passion, for he may passionately defend something like evolution against those who do not see that the evidence is overwhelmingly strong. His hostility is then naturally against fundamentalist religion because it teaches people not to change their minds or see the exciting things available to be known. He sees an unavoidable conflict between science and religion, and believes science to be hindered by fundamentalist religion. He concedes that non-fundamentalist religion may not be doing that, but he also says that it fosters fundamentalism by teaching children that unquestioning faith is a virtue. Dawkins proceeds to look at examples crimes under religious law that he does not consider crimes, namely blasphemy and homosexuality, and thus nowhere near worthy of the punishment of death. His idea is that they are not hurting anybody and are only doing private things and having their own private thoughts, and should not be condemned as evil. Dawkins is especially disdainful toward those he calls the American Taliban, who want a theocracy in America and to do away with what was called evil. Moving on to abortion, Dawkins cannot understand why religion would speak out against killing an embryo, but have no problem taking adult life, in the examples described above. Euthanasia is a similar issue and both have “slippery slope” arguments against them, or in other words, “Where does the killing stop?” or if you are willing to kill babies in the womb, what about infanticide or if you kill invalids, what about your granny to get her money? Dawkins submits that the consequences of such actions may be better than some absolutism, as he portrays the irony of what some fundamentalists defend on the basis of religion. He gives the story of Reverend Paul Hill, who killed a doctor and his bodyguard with a shotgun to prevent the future deaths of innocent babies. Dawkins does recognize that not all religious people are like this, but he does conclude the chapter with a more lengthy discussion of how moderation in faith fosters fanaticism than what he briefly stated at the beginning of the chapter. On Christian example given is that of those who believe in the rapture, leading to their belief that Israel has a God-given claim to the land of Palestine or to the longing for nuclear war, seeing it as Armageddon and necessary before the return of Christ. Turning to a suicide bomb attack in London a few years ago, Dawkins describes the murderers on page 342 as “British citizens, cricket-loving, well-mannered, just the sort of young men whose company one might have enjoyed.” Dawkins concedes that patriotism and love for one’s own ethnic group may produce similar results in regard to devotion of life to extremism, but religion is described as especially potent, because it says death is not the end, a martyr’s heaven is glorious, and it discourages questioning by its very nature. It is this teaching, that faith itself is a virtue without requiring justification or argument, that Dawkins considers particularly evil, and especially in regard to teaching this to children, to which he turns in the next chapter.

Dawkins said earlier that he does not believe that any child should be labeled with the religious belief that their parents hold, and the title of chapter 9 is Childhood, abuse and the escape from religion. In this vein, he opens with an anecdote about a young boy of Jewish parents in the middle of the 19th century. This boy was dragged away from his parents under legal authority from the Inquisition, carried out by papal police. He was then taken to a house for the conversion of Jews and Muslims in Rome and brought up as a Roman Catholic. The reason he was taken was a policy of the Catholic church concerning children that had been baptized, for after becoming sick, he was baptized out of fear that he might die by his 14 year old Catholic caretaker. The idea was that, after learning years later that this young boy had officially become a Christian because of this baptism, he could not be left to be raised by Jewish parents. To Dawkins, this is an example of the religious mind and the evils that arise specifically because it is religious. He avoided such topics such as the horrors of the Crusades, because he recognizes evil people pop up everywhere and can be of every persuasion, but he has a serious problem with a mindset that think a sprinkling of water and an utterance of words can completely change a child’s life, all against parental consent, the child’s consent, and even the child’s happiness and well-being. He also has a serious problem with the view of popes and cardinals about the practice being protection and not anything terrible at all. Thirdly, he is also resistant to the notion that, as described on page 353, “religious people know, without evidence, that the faith of their birth is the one true faith, all others being aberrations or downright false.” Lastly, in addition to it being against his opinion that a child could change his religious beliefs in a moment not involving his consent, he is again against the labeling of that same child in the first place with any particular beliefs, having had insufficient time to have thought them out rationally. Turning to the physical and mental abuse, Dawkins addresses priestly abuse of children in terms of sexual abuse first, which is how it is perceived today, and even describes that he was in fact a victim of one of them, which he describes as embarrassing but otherwise harmless. As he develops the idea further, it becomes clear that his point is how psychological abuse can be worse than physical. A letter he received described how a woman brought up Catholic was sexually abused by a priest when she was seven and this made her feel “yucky”, but the memory of a friend who had died going to hell because she was a Protestant was one of cold, immeasurable fear. Speaking of which, the idea of hell itself is another example of Dawkins’ concept of child abuse, seeing the idea as an attempt to scare the children witless of what will happen after they die, if they had lived a life of sin. In terms of escaping from these sort of things, there is an idea that to become an atheist is to be ostracised by one’s family and friends. It is something that people sometimes have a gradual progression from not knowing whether they are allowed to not believe in God, to not believing while just not telling anyone, to finally confessing that they are atheists, to which the response is usually disillusionment. Moving on, examples are shared about how children are subjected to religious views, from the Amish in America to a school teaching creationism funded by Tony Blair in Britain, but the point is the same, namely that exclusive beliefs are being stuffed down young, impressionable throats. Returning to the concept of consciousness-raising, a Christmas news article described a school play of the nativity, with the Three Wise Men being played by Shadbreet (a Sikh), Musharaff (a Muslim) and Adele (a Christian), all 4 years old. Dawkins is disgusted by this and illustrates the point by saying that if they were labeled a Keynesian, a Monetarist, and a Marxist, all aged 4, people would protest. However, since it is religious, Dawkins suggests that it is perceived to be above criticism. Rounding off the chapter, Dawkins shows that he is not suggesting that the Bible be thrown out, because of its value in literature and how people can observe the traditions such as marriages and funerals without subscribing to supernatural beliefs, giving up belief in God without throwing away a treasured heritage.

The final chapter, titled A much needed gap?, contains a double meaning, because Dawkins has ridiculed how Christians used God as the “God of the gaps” to fill the holes in science and in the human longing that seemed to only be explained by a supernatural, transcendent Being. However, the title was applied to Dawkins book to the effect that it bridges what people were looking for, perhaps in terms of raising consciousness in an area that many were looking into already. On the other side, the suggestion is made that God clutters up a gap better filled with something else. Religion was thought to offer explanation, exhortation, consolation, and inspiration, but Dawkins either has or will argue for the lack of necessity for religion being that and for what he feels should take that place. Starting with explanation, he says that he explained his view of science superseding the need for God in chapter 4 and by exhortation he means moral instruction, which he feels to be covered in chapters 6 and 7. Consolation is what he will take on next in this chapter, introduced by a discussion of imaginary friends, referred to as Binker due to a poem by A.A. Milne. The question becomes such as this, that if God does not exist, what is going to be put in His place in terms of consolation and the need for God. Dawkins makes himself very clear that need for something does not make it true, and would indeed rather submit that people fell the need to believe in belief rather than believe in God, or in other words, remain favourable to the idea of people believing, regardless of the truth of the matter. Less concerned with whether belief has an effect on happiness, Dawkins would like to explore whether there is any good reason to feel depressed if people live without God. Consolation is defined as 1. Direct physical consolation and 2. Consolation by discovery of a previously unappreciated fact, or a previously undiscovered way of looking at existing facts. Comparing religion with science, imagining God’s arms could console in the same way as a real friend, but the suggestion is that scientific medicine can also offer comfort. Turning to number 2, religion can offer consolation is times of trouble, believing that God will work things out in the fullness of time and that ultimately, heaven awaits. Tied to this is Dawkins wondering why religious people are still afraid of death and why they oppose euthanasia for similar reasons. It is further suggested that those who are afraid of death tend to be religious, at least based on a few observations in different accounts. However, the point is that life can be as meaningful as people choose to make it and that science may provide this consolation and even inspiration as he moves on to explain. Accordingly to purely scientific perspectives, Dawkins shares how fortunate the lives that get lived are and how it should not be wasted, for that would not do justice to the trillions of unborn who were not so lucky, in that they did not live in the first place. Having only one life should make it all the more precious as well. Using the imagery of a burka, the Muslim women’s dress which includes a small eye slit in the most extreme style, Dawkins envisions science as an agent to open up understanding and widen the view from the ancestrally familiar. Dawkins describes the wonder of science in finding things out from the strange happenings of quantum mechanics to the molecular theories of how the same molecules that exist now in their present form existed in the times of the dinosaurs, though in a different sense. He describes how reality is a perceived concept, seeing a rock as solid because we cannot put our hand through it, but a whirlpool as not solid for similar reasons. People can relate to the world around us based on how we were so far made to understand it, but just like the concepts of people like Galileo did not seem to make sense because of the way people saw the world, these mysteries can be sought out through science. The thought is to possibly tear off the burka in exploration as the realm of possibility expands. After asking if this is the future, Dawkins last word in the book is “I am thrilled to be alive at time when humanity is pushing against the limits of understanding. Even better, we may eventually discover that there are no limits.”

So if it is raising consciousness that Dawkins has intended to do, I think he has been successful in that. He has testified to the fact that people have found release from religion through his book, but has he also stirred up those who did not previously think that the question of God’s existence was significant or even open to debate? I realize that this was a long article, but I truly hope you have read it to the end, for I think it is as relevant as it is thought-provoking. I began by saying that Paul knew his audience and communicated Christ to them, understanding the way they thought, and I think it best to leave you with a quote from him. Acts 17:22-31 “22So Paul, standing in the midst of the Areopagus, said: “Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. 23For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription, ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. 24 The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, 25nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything. 26And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, 27 that they should seek God, in the hope that they might feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, 28for

“‘In him we live and move and have our being’;

as even some of your own poets have said,

“‘For we are indeed his offspring.’

29 Being then God’s offspring, we ought not to think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man. 30 The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent, 31because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.”

Is God a delusion? In my next article, I will have some things to say about that, and I sincerely hope that every follower of Jesus Christ would have something to say as well.

Click here to see part 1 in response to the first 5 chapters of The God Delusion.

reference to evolutionists, geneticist Richard Lewontin says that they “have a prior commitment, a commitment to naturalism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counter-intuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.” (Billions and Billions of Demons in The New York Review, p.31). There are those who are honest enough to express that they do not know how the universe came into existence, but like Lewontin, they are sure it has nothing to do with God.

reference to evolutionists, geneticist Richard Lewontin says that they “have a prior commitment, a commitment to naturalism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counter-intuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.” (Billions and Billions of Demons in The New York Review, p.31). There are those who are honest enough to express that they do not know how the universe came into existence, but like Lewontin, they are sure it has nothing to do with God. urpose there may be is what we make for ourselves by virtue of our highly developed evolutionary status as a species.

urpose there may be is what we make for ourselves by virtue of our highly developed evolutionary status as a species. scoveries such as the expansion of the universe, the second law of thermodynamics, and Einstein’s theory of general relativity, or they end up saying that the universe brought itself into existence out of nothing. Geisler and Turek rightly bring this to its logical conclusion. “Either someone created something out of nothing (the Christian view), or no one created something out of nothing (the atheistic view). Which view is more reasonable? The Christian view. Which view requires more faith? The atheistic view.” (I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist, p.26). With the belief, and it is a belief, that the universe caused itself to exist goes the belief that there was something before the Big Bang, but nothing really means nothing and not some form of something. Furthermore, what about the naturalistic understanding of the origin of information, order coming from disorder? DNA is complex by anyone’s reckoning and yet, it must have arisen by natural processes on the atheistic worldview.

scoveries such as the expansion of the universe, the second law of thermodynamics, and Einstein’s theory of general relativity, or they end up saying that the universe brought itself into existence out of nothing. Geisler and Turek rightly bring this to its logical conclusion. “Either someone created something out of nothing (the Christian view), or no one created something out of nothing (the atheistic view). Which view is more reasonable? The Christian view. Which view requires more faith? The atheistic view.” (I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist, p.26). With the belief, and it is a belief, that the universe caused itself to exist goes the belief that there was something before the Big Bang, but nothing really means nothing and not some form of something. Furthermore, what about the naturalistic understanding of the origin of information, order coming from disorder? DNA is complex by anyone’s reckoning and yet, it must have arisen by natural processes on the atheistic worldview.  Former atheist Antony Flew records his experience of being shown the fallacy of the oft-quoted “monkey theorem”, the idea that monkeys banging away on keyboards could eventually end up writing a Shakespearean sonnet. “Schroeder first referred to an experiment conducted by the British National Council of Arts. A computer was placed in a cage with six monkeys. After one month of hammering away at it (as well as using it as a bathroom!), the monkeys produced fifty typed pages — but not a single word. Schroeder noted that this was the case even though the shortest word in the English language is one letter (a or I). A is a word only if there is a space on either side of it. If we take it that the keyboard has thirty characters (the twenty-six letters and other symbols), then the likelihood of getting a one-letter word is 30 times 30 times 30, which is 27,000. The likelihood of getting a one-letter word is one chance out of 27,000.” (There Is A God, p.76). I could also mention again the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus and the origin of the Christian faith, which makes naturalism’s rejection of the miraculous untenable if the resurrection actually did happen in history. Other examples could be cited, but the point is that for a belief system that is supposedly only concerned with the facts, there are certainly a lot of gaps. Theists are often accused of using “God of the gaps” as an argument and saying that God must have done whatever we do not yet understand about the universe. However, I hope I have sufficiently pointed out that there are things we do know about the universe that are inconsistent with naturalism, without any reference to God.

Former atheist Antony Flew records his experience of being shown the fallacy of the oft-quoted “monkey theorem”, the idea that monkeys banging away on keyboards could eventually end up writing a Shakespearean sonnet. “Schroeder first referred to an experiment conducted by the British National Council of Arts. A computer was placed in a cage with six monkeys. After one month of hammering away at it (as well as using it as a bathroom!), the monkeys produced fifty typed pages — but not a single word. Schroeder noted that this was the case even though the shortest word in the English language is one letter (a or I). A is a word only if there is a space on either side of it. If we take it that the keyboard has thirty characters (the twenty-six letters and other symbols), then the likelihood of getting a one-letter word is 30 times 30 times 30, which is 27,000. The likelihood of getting a one-letter word is one chance out of 27,000.” (There Is A God, p.76). I could also mention again the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus and the origin of the Christian faith, which makes naturalism’s rejection of the miraculous untenable if the resurrection actually did happen in history. Other examples could be cited, but the point is that for a belief system that is supposedly only concerned with the facts, there are certainly a lot of gaps. Theists are often accused of using “God of the gaps” as an argument and saying that God must have done whatever we do not yet understand about the universe. However, I hope I have sufficiently pointed out that there are things we do know about the universe that are inconsistent with naturalism, without any reference to God. Lurking behind all this is the evolutionary aspect to society, as naturalists see it. They say they do not need God to be good. They live morally anyway and for the most part have similar values to the Christian worldview. A few things could be mentioned in regard to this. Ravi Zacharias states, “Any antitheist who lives a moral life merely lives better than his or her philosophy warrants.” (Can Man Live Without God, p.32). The evolutionary worldview is based on survival of the fittest and is red in tooth and claw. “An ethic of moral autonomy and individual rights, so important to secular liberals, is incapable of sustaining and nourishing values such as altruism and self-sacrifice.” (Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster?, p.212). Copan also catches Dawkins in his discussions on morality in The God Delusion. Copan observes that “…Dawkins is helping himself to the metaphysical resources of a worldview he repudiates.” (Is God a Moral Monster?, p.210). The West is built on biblical values, so naturally, those in such societies do not differ too drastically. However, it could also be said that it is not that people cannot be good without belief in God, for there are moral atheists, and what is more, immoral Christians, but the belief is not that we are good because we believe in God, but rather that God has created us with a conscience, an innate sense of right and wrong. Though not exhaustive or specific, there is a general sense of the fact that some things are just wrong and we know it. What about the belief that humans are basically good? Ravi Zacharias is again insightful. “Any philosophy that has built its social structure assuming an innate goodness finds its optimism ever disappointed.” (Can Man Live Without God, p.133). “Conveniently forgotten by those antagonistic to spiritual issues are the far more devastating consequences that have entailed when antitheism is wedded to political theory and social engineering.” (Can Man Live Without God, p.xvii).The 19th century produced some interesting ideas, from Nietzsche’s superman to Marx’s Communism, both rejecting God as a basis for anything. However, in practice, these views saw the deaths of millions in Nazi Germany and the Communist states. One of those affected by Communism had this to say after seeing the implications of just beliefs: “It was because we rejected the doctrine of original sin that we on the Left were always being disappointed…” (C.E.M. Joad, quoted in Counterfeit Gods, p.105). There was this hope that the state would dissolve away and there would be no government, but this view did not take into account that man is sinful and generally selfish. Power has corrupted many a well-intentioned man and will continue to do so if we do not realize that we are not as good as we think we are.

Lurking behind all this is the evolutionary aspect to society, as naturalists see it. They say they do not need God to be good. They live morally anyway and for the most part have similar values to the Christian worldview. A few things could be mentioned in regard to this. Ravi Zacharias states, “Any antitheist who lives a moral life merely lives better than his or her philosophy warrants.” (Can Man Live Without God, p.32). The evolutionary worldview is based on survival of the fittest and is red in tooth and claw. “An ethic of moral autonomy and individual rights, so important to secular liberals, is incapable of sustaining and nourishing values such as altruism and self-sacrifice.” (Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster?, p.212). Copan also catches Dawkins in his discussions on morality in The God Delusion. Copan observes that “…Dawkins is helping himself to the metaphysical resources of a worldview he repudiates.” (Is God a Moral Monster?, p.210). The West is built on biblical values, so naturally, those in such societies do not differ too drastically. However, it could also be said that it is not that people cannot be good without belief in God, for there are moral atheists, and what is more, immoral Christians, but the belief is not that we are good because we believe in God, but rather that God has created us with a conscience, an innate sense of right and wrong. Though not exhaustive or specific, there is a general sense of the fact that some things are just wrong and we know it. What about the belief that humans are basically good? Ravi Zacharias is again insightful. “Any philosophy that has built its social structure assuming an innate goodness finds its optimism ever disappointed.” (Can Man Live Without God, p.133). “Conveniently forgotten by those antagonistic to spiritual issues are the far more devastating consequences that have entailed when antitheism is wedded to political theory and social engineering.” (Can Man Live Without God, p.xvii).The 19th century produced some interesting ideas, from Nietzsche’s superman to Marx’s Communism, both rejecting God as a basis for anything. However, in practice, these views saw the deaths of millions in Nazi Germany and the Communist states. One of those affected by Communism had this to say after seeing the implications of just beliefs: “It was because we rejected the doctrine of original sin that we on the Left were always being disappointed…” (C.E.M. Joad, quoted in Counterfeit Gods, p.105). There was this hope that the state would dissolve away and there would be no government, but this view did not take into account that man is sinful and generally selfish. Power has corrupted many a well-intentioned man and will continue to do so if we do not realize that we are not as good as we think we are.  Darrow Miller sums this up well. “The events of the past hundred years-the two world wars, the genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda, the ethnic cleansing in the Balkans in the nineties and the planned famines in the Ukraine in the thirties, the inhumanity of Mao and Stalin, apartheid in South Africa, and the deliberate murder of hundreds of millions of preborn babies through abortion-all deny the utopian view of the materialist.” (LifeWork, p.44). The 20th century saw more people die in war than all the previous centuries of recorded history put together (105 million deaths, compared with 19.4 million in the 19th century and 7 million in the 18th). As if this were not enough, according to the naturalist, all these people simply ceased to exist as persons. There is no hope that any of them found peace, rest, and salvation after death. Not to say that the Christian view of the afterlife must be true because it makes believers in Jesus feel better, but if I were to accept the naturalistic view of the world, I would have to see a lot more compelling evidence, for it does not seem to me to be particularly consistent nor hopeful as a worldview. In fact, it currently seems to be in a place of denial. I might even go so far as to concur facetiously with Alister McGrath in reference to Richard Dawkins and his book The God Delusion, “Might atheism be a delusion about God?” (The Dawkins Delusion?, p.65) (for more on Dawkins’ views click here and for subsequent responses to those views click here).

Darrow Miller sums this up well. “The events of the past hundred years-the two world wars, the genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda, the ethnic cleansing in the Balkans in the nineties and the planned famines in the Ukraine in the thirties, the inhumanity of Mao and Stalin, apartheid in South Africa, and the deliberate murder of hundreds of millions of preborn babies through abortion-all deny the utopian view of the materialist.” (LifeWork, p.44). The 20th century saw more people die in war than all the previous centuries of recorded history put together (105 million deaths, compared with 19.4 million in the 19th century and 7 million in the 18th). As if this were not enough, according to the naturalist, all these people simply ceased to exist as persons. There is no hope that any of them found peace, rest, and salvation after death. Not to say that the Christian view of the afterlife must be true because it makes believers in Jesus feel better, but if I were to accept the naturalistic view of the world, I would have to see a lot more compelling evidence, for it does not seem to me to be particularly consistent nor hopeful as a worldview. In fact, it currently seems to be in a place of denial. I might even go so far as to concur facetiously with Alister McGrath in reference to Richard Dawkins and his book The God Delusion, “Might atheism be a delusion about God?” (The Dawkins Delusion?, p.65) (for more on Dawkins’ views click here and for subsequent responses to those views click here).