By Matt Lefebvre

This post is a continuation of the series on the reliability of the Bible. Please see the introduction if you have not read it yet.

Introduction

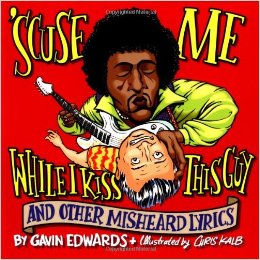

Have you ever been singing a song, but then forgot some of the lyrics? It happens to me sometimes, but I have even seen examples of people thinking that they are singing the correct lyrics, when in reality, they are not even close. However, it does not even have to be a huge difference in wording to drastically change the meaning of a song. I recently saw a list of the Top Ten Misheard Lyrics and some of them become quite comical when altered from the original. Some examples are in order.

A line from Elton John’s song Tiny Dancer, “Hold me closer tiny dancer”, has been misinterpreted as “Hold me closer Tony Danza”.

A line from Elton John’s song Tiny Dancer, “Hold me closer tiny dancer”, has been misinterpreted as “Hold me closer Tony Danza”.

In Black Sabbath’s song Paranoid, “I tell you to enjoy life” has been mistakenly thought to be “I tell you to end your life” by some.

Jimmy Hendrix’s song Purple Haze includes the line “’Scuse me, while I kiss the sky” which is sometimes incorrectly changed to “’Scuse me, while I kiss this guy”. In fact, there is even a website called kissthisguy.com devoted to similar instances of misheard lyrics.

Examples like this could be multiplied, for, whether through misinformation, mishearing, or just plain old forgetfulness, we do not always get all the details right.

Now the examples I have given range in seriousness. On the one end, some parents have blamed Ozzy Osbourne (who was the lead singer of Black Sabbath at the time of the song) for select suicides, and on the other end, a couple of sitcoms (Friends, Will and Grace) have had some good fun with the Elton John parody.  Jimmy Hendrix even had some fun with his own misheard line by singing the misheard version, “’Scuse me, while I kiss this guy”, during a concert and pointing to his guitarist. Though I do generally think that it is important to get things right, I think the significance is multiplied when we turn our attention to the Bible. In part 1 of this series, I gave reasons for believing that God really has spoken in history and that these words are recorded in the Bible. However, even if someone concedes that God did speak some things at certain times, is there further reason to believe that those words were recorded accurately? After all, the evidence I gave in defense of the Bible claiming to be from God was more general. I think it at least shows that God has spoken in history, but are we able to say more by assessing the quality of the recorders of that history? From one perspective, perhaps Jesus did speak the truth from God, but the four Gospels have obscured that message. From another perspective, perhaps our understanding of the general reliability of the Gospels will bring us back to trusting the purity of the message as communicated from God.

Jimmy Hendrix even had some fun with his own misheard line by singing the misheard version, “’Scuse me, while I kiss this guy”, during a concert and pointing to his guitarist. Though I do generally think that it is important to get things right, I think the significance is multiplied when we turn our attention to the Bible. In part 1 of this series, I gave reasons for believing that God really has spoken in history and that these words are recorded in the Bible. However, even if someone concedes that God did speak some things at certain times, is there further reason to believe that those words were recorded accurately? After all, the evidence I gave in defense of the Bible claiming to be from God was more general. I think it at least shows that God has spoken in history, but are we able to say more by assessing the quality of the recorders of that history? From one perspective, perhaps Jesus did speak the truth from God, but the four Gospels have obscured that message. From another perspective, perhaps our understanding of the general reliability of the Gospels will bring us back to trusting the purity of the message as communicated from God.

The Reliability of the Gospels

In considering the question of whether the right words were written down, I have chosen to focus on the Gospels for a few reasons. I mentioned in the introduction to this series that I would pay more attention to the New Testament than the Old Testament. This is both because there is more that we know about the time of the New Testament for us to evaluate, being nearer in time, and because the New Testament bears witness to the Old Testament.

In considering the question of whether the right words were written down, I have chosen to focus on the Gospels for a few reasons. I mentioned in the introduction to this series that I would pay more attention to the New Testament than the Old Testament. This is both because there is more that we know about the time of the New Testament for us to evaluate, being nearer in time, and because the New Testament bears witness to the Old Testament.

Second, though there are other books in the New Testament, the letters do not have many historical references for evaluation. The Gospels (and I could add the book of Acts), however, present narratives that could be questioned or confirmed based on coherence with history.

Third, there are four Gospels, so this allows them to be examined side by side and compared to establish a level of internal consistency. They can be read vertically, looking at the consistency of a Gospel within itself, but also horizontally, looking at the consistency of a Gospel compared with the other three.

Finally, the Gospels, for different reasons, have been the target of considerable opposition, especially in recent decades. This opposition has great significance, wherever the evidence may lead.  Because the Gospels are narratives of the life and teaching of Jesus Christ, the central figure of Christianity (the very One from whom the name “Christian” is derived), to largely discredit these narratives would be to largely discredit Christianity itself. According to the Bible’s own testimony, Jesus is the fulfillment of the Old Testament (Matthew 5:17) and the Christ, the Son of God (Matthew 26:63-64), and verses emphasizing the centrality of Christ to the Christian faith could be multiplied. However, the Apostle Paul makes very clear that this faith could be falsified if Christ has not been raised from the dead (1 Corinthians 15:14, 17), while at the same time strongly asserting that Christ has been raised (1 Corinthians 15:20). This very important detail of Christ’s life is recorded in the Gospels, among others, so it is certainly worth considering if this information is reliable. However, the knife of critical examination cuts both ways, and this is why I said above that the opposition has great significance. It is not only the case that discrediting the Gospels would have implications for the Christian, but also that confirming the Gospels would have implications for the skeptic. After all, if the kinds of things that Jesus said and did were shown to be accurately recorded history, it would demand a response from all who read it, regardless of their predispositions.

Because the Gospels are narratives of the life and teaching of Jesus Christ, the central figure of Christianity (the very One from whom the name “Christian” is derived), to largely discredit these narratives would be to largely discredit Christianity itself. According to the Bible’s own testimony, Jesus is the fulfillment of the Old Testament (Matthew 5:17) and the Christ, the Son of God (Matthew 26:63-64), and verses emphasizing the centrality of Christ to the Christian faith could be multiplied. However, the Apostle Paul makes very clear that this faith could be falsified if Christ has not been raised from the dead (1 Corinthians 15:14, 17), while at the same time strongly asserting that Christ has been raised (1 Corinthians 15:20). This very important detail of Christ’s life is recorded in the Gospels, among others, so it is certainly worth considering if this information is reliable. However, the knife of critical examination cuts both ways, and this is why I said above that the opposition has great significance. It is not only the case that discrediting the Gospels would have implications for the Christian, but also that confirming the Gospels would have implications for the skeptic. After all, if the kinds of things that Jesus said and did were shown to be accurately recorded history, it would demand a response from all who read it, regardless of their predispositions.

In light of this, I intend to go about making a case for the reliability of the Gospels by starting with a little perspective, comparing the Gospels to other ancient histories and works in terms of historical standards. I will also look at the Gospels individually in terms of historical accuracy. Then I will examine the Gospels together in terms of internal consistency. That will be the extent of this article, but because of the above mentioned objections, I will also address common objections in the accompanying article, for those who are interested.

A History Lesson

How Did We Get the Gospels?

While this may not be a question that people are used to asking, it is an important one for evaluating the historicity of the Gospels.  After all, we must first get an idea of the process of transmission before we can assess its reliability. If you were thinking of Jesus teaching while a stenographer types down every word He says, think again. However, just because a modern method of the transmission of information was not in place, it does not mean nothing was in place or that the transmission of information was unreliable. Though different stages have been suggested by different scholars for the writing of the Gospels, I would like to focus on the period of oral transmission. I will do so because it is the period people would generally consider to be less reliable than the written period and because there could be misunderstandings concerning the reliability of oral history.

After all, we must first get an idea of the process of transmission before we can assess its reliability. If you were thinking of Jesus teaching while a stenographer types down every word He says, think again. However, just because a modern method of the transmission of information was not in place, it does not mean nothing was in place or that the transmission of information was unreliable. Though different stages have been suggested by different scholars for the writing of the Gospels, I would like to focus on the period of oral transmission. I will do so because it is the period people would generally consider to be less reliable than the written period and because there could be misunderstandings concerning the reliability of oral history.

Oral Compared with Written History

One aspect of oral history that may surprise you is that, in some ways, oral history was actually preferable to written history in the ancient world. A good reason for this would be that a written account of something was set, while a verbal account could be given further explanation if necessary.

As Timothy Paul Jones puts it, “In some cases, first-century folk may have been less likely to trust written records, because they couldn’t speak personally with the individual that was telling the story!” (Misquoting Truth, p.85). At first, this might give the impression that a verbal account is taking liberties with what would have been written down in a book. However, this is forgetting that written accounts can often be limited in scope.  To give an illustration, have you ever asked yourself why we have history teachers? After all, if we have a history textbook, can we not simply read the book and know all we need to about the subject? If you answered yes, I fear it might have more to do with not liking your history teacher than actually thinking there is no more to history than what can be recorded in a book. However, my point is that the teacher is there to give context, point to the significance of events, answer questions that come up, and so on. Turning our attention to the Gospels, we must begin to realize that these accounts of Jesus’ life and teaching are very selective. John 20:30 and 21:25 tell us as much.

To give an illustration, have you ever asked yourself why we have history teachers? After all, if we have a history textbook, can we not simply read the book and know all we need to about the subject? If you answered yes, I fear it might have more to do with not liking your history teacher than actually thinking there is no more to history than what can be recorded in a book. However, my point is that the teacher is there to give context, point to the significance of events, answer questions that come up, and so on. Turning our attention to the Gospels, we must begin to realize that these accounts of Jesus’ life and teaching are very selective. John 20:30 and 21:25 tell us as much.

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book”

“Now there are also many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.”

We are also informed by the Gospels themselves that Jesus explained things privately to His disciples. Mark 4:34 is a representative example, but there are many more instances where Jesus teaches the crowds, while telling more to His closest followers. It makes sense if you think about it. If the Gospels contained everything Jesus ever said and did, we would have to conclude that Jesus did not say or do many things, especially considering that the majority of His life before He was 30 years old is not recorded. However, our concern is mostly with what is recorded and with the reliability of this witness to what happened.

One person in the early church who appreciated the value of this witness was a bishop of Hierapolis, named Papias. He lived in the second half of the 1st century, when some of the disciples of Jesus still lived, but he also lived on into the 2nd century. Papias talks about how he sought what the disciples had said, asking those who had heard them. Looking back on his encounters with those who heard their words and speaking about what came from the disciples, he said,

“For I perceived that what was to be obtained from books would not profit me as much as what came from the living and surviving voice.” (Quoted in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 3.39)

Papias is not saying that books are somehow unreliable, because that would undermine the reliability of the Gospels. What he is saying is that he would rather hear the testimony of the disciples themselves. This would not be possible forever, of course, because the disciples of Jesus did eventually die, but it is significant that this oral history of what Jesus did and taught was so highly valued.

Regulating Oral History

This leads into another important point to make about oral history, which is the fact that not just any story was considered oral history. A person was not free to make up a story about Jesus or to change what had been proclaimed. In terms of what was considered oral history,

Richard Bauckham, a professor of New Testament Studies, points out how a distinction was made in oral societies between tales and accounts.

“…oral societies treat historical tales and historical accounts differently and in such a way that the latter are preserved more faithfully.” (Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.273)

If we imagine every story in the ancient world to have been accorded the same historical value by the ancients themselves, we would be quite mistaken. Professor of New Testament Craig Keener points out several ancient authors who differentiated between what was historical and what was fantasy.  Among them is Arrian, who, in his biography of Alexander the Great, complained that some writers tell of wonders at the ends of the earth only because they can get away with inventing stories that their readers cannot check. Diodorus Siculus even attempted to “demythologize” some accounts, depicting how he saw accounts reworked into mythological ones. Thucydides claimed to deal with probable events, rather than the pleasant-sounding myths. Livy warns that the more incredible reports are believed, the more others will spring up, implicitly distinguishing those spurious accounts from his own.

Among them is Arrian, who, in his biography of Alexander the Great, complained that some writers tell of wonders at the ends of the earth only because they can get away with inventing stories that their readers cannot check. Diodorus Siculus even attempted to “demythologize” some accounts, depicting how he saw accounts reworked into mythological ones. Thucydides claimed to deal with probable events, rather than the pleasant-sounding myths. Livy warns that the more incredible reports are believed, the more others will spring up, implicitly distinguishing those spurious accounts from his own.

Perhaps the clearest illustration is found in a quote from Plutarch, who himself encouraged neither believing too much nor disbelieving too much (Miracles, p.90-92), for he said,

“Whenever you hear the traditional tales which the Egyptians tell about the gods, their wanderings, their dismemberments, and many experiences of the sort,…you must not think that any of these tales actually happened in the manner in which they are related.” (Quoted in J. Ed Komoszewski, M. James Sawyer, and Daniel Wallace, Reinventing Jesus, p.252).

So we can see that there was a difference, but how does the oral history of Jesus’ disciples distinguish itself as different from tales? Tales could develop from some historical core that was embellished over time, or they could be entirely made up to explain something through the use of a story. The oral history spread by the disciples of Jesus distinguishes itself by close proximity to the events described. So not just any person could make up a story about Jesus and have it become oral history, because the followers of Jesus were around to correct them.  Before the Gospels were written, the disciples were not just sitting around waiting for them to be written, but they were proclaiming the message about Jesus that would eventually be written down in the Gospels.

Before the Gospels were written, the disciples were not just sitting around waiting for them to be written, but they were proclaiming the message about Jesus that would eventually be written down in the Gospels.

“…the interval between Jesus and the written Gospels was not dormant. The apostles and other eyewitnesses were proclaiming the good news about Jesus Christ wherever they went.” (J. Ed Komoszewski, M. James Sawyer, and Daniel Wallace, Reinventing Jesus, p.34)

We can see hints of this in other parts of the New Testament. The Apostle Paul writes a few references to traditions of Jesus in 1 Corinthians, written around the mid-50’s. 1 Corinthians 9:14 makes a reference to the Lord’s command, which is very likely referring to what Jesus says in Luke 10:7, that “the laborer deserves his wages”, and this is even quoted more explicitly in Paul’s 1st letter to Timothy (5:18).  Paul’s description of the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 is quite similar to the words of the Lord Jesus recorded in Luke 22:19-20. There are other references, such as 1 Corinthians 7:10 and 15:1-5, but I want to pay special attention to the parallels in Luke. 1 Corinthians was written before Luke and very likely before any of the Gospels, so it is not as if Paul is simply quoting from a Gospel here. It may be that Paul and Luke draw from the same oral history. I cannot prove that these parallels come from the same source, but even if they do not, that only strengthens the case for the idea of a uniform oral history before the writing of the Gospels. That would mean that Paul and Luke drew the same saying of Jesus from different sources.

Paul’s description of the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 is quite similar to the words of the Lord Jesus recorded in Luke 22:19-20. There are other references, such as 1 Corinthians 7:10 and 15:1-5, but I want to pay special attention to the parallels in Luke. 1 Corinthians was written before Luke and very likely before any of the Gospels, so it is not as if Paul is simply quoting from a Gospel here. It may be that Paul and Luke draw from the same oral history. I cannot prove that these parallels come from the same source, but even if they do not, that only strengthens the case for the idea of a uniform oral history before the writing of the Gospels. That would mean that Paul and Luke drew the same saying of Jesus from different sources.

There are also examples of people trying to teach what was not true of Jesus, in opposition to the disciples. In 1 John 2:22 and 4:2-3 we see indications that there was a false teaching about Jesus that needed to be corrected. The authority for this correction comes from the firsthand nature of the testimony about Jesus (1 John 1:1-4). Paul encouraged a confused church at Colossae to not be led astray according to human tradition, but to follow Christ (Colossians 2:8-9). Examples of the teaching of Jesus, either explicitly or implicitly, in the writings of the New Testament outside the Gospels could be multiplied, but the point is that the witness of the disciples was being preserved, through proclamation of the truth and rebuke of false teaching.

There are also examples of people trying to teach what was not true of Jesus, in opposition to the disciples. In 1 John 2:22 and 4:2-3 we see indications that there was a false teaching about Jesus that needed to be corrected. The authority for this correction comes from the firsthand nature of the testimony about Jesus (1 John 1:1-4). Paul encouraged a confused church at Colossae to not be led astray according to human tradition, but to follow Christ (Colossians 2:8-9). Examples of the teaching of Jesus, either explicitly or implicitly, in the writings of the New Testament outside the Gospels could be multiplied, but the point is that the witness of the disciples was being preserved, through proclamation of the truth and rebuke of false teaching.

The Gospels Compared with Other Ancient History

In addition to not being dormant, but filled with oral history, the interval of time between the time of Jesus and the writing of the Gospels was not even relatively long. When some people hear the generally accepted dates for the Gospels, about 30-70 years after Jesus (Mark Roberts, Can We Trust the Gospels?, p.58), they think it sounds like a considerable amount of time. Would accurate oral history be able to be preserved over this time period? Philosopher William Lane Craig references a well-known historian to answer that question.

In addition to not being dormant, but filled with oral history, the interval of time between the time of Jesus and the writing of the Gospels was not even relatively long. When some people hear the generally accepted dates for the Gospels, about 30-70 years after Jesus (Mark Roberts, Can We Trust the Gospels?, p.58), they think it sounds like a considerable amount of time. Would accurate oral history be able to be preserved over this time period? Philosopher William Lane Craig references a well-known historian to answer that question.

“Roman historian A. N. Sherwin-White remarks that in classical historiography the sources are usually biased and removed at least one or two generations or even centuries from the events they narrate, but historians still reconstruct with confidence what happened. In the Gospels, by contrast, the tempo is ‘unbelievable’ for the accrual of legend; more generations are needed. The writings of Herodotus enable us to test the tempo of myth-making, and the tests suggest that even two generations are too short a span to allow the mythical tendency to prevail over the hard historic core of oral tradition. Such a gap with regard to the Gospel traditions would land us in the second century, precisely when the apocryphal Gospels began to originate.” (William Lane Craig, in J.P. Moreland and Michael Wilkins, Jesus Under Fire, p.154)

So if history can be accurately constructed based on sources a couple generations, or even centuries, after the actual events, great confidence can certainly be put in the Gospels in terms of their close proximity to the time of Jesus. Some may claim that the Gospels present legendary accounts of Jesus, made up long after the events, but the claim of legend goes against the evidence and “long” must be understood in a relative manner.  This is further strengthened by the fact that when we see Gospels outside the New Testament starting to fit the profile of legend, it is in the second century, long after the people who actually followed Jesus were no longer living. I will have more to say about these so-called Gospels later in this series, but it is enough to notice here that the poor quality of the apocryphal Gospels, those outside the Bible, serves to indirectly confirm the good quality of the biblical Gospels.

This is further strengthened by the fact that when we see Gospels outside the New Testament starting to fit the profile of legend, it is in the second century, long after the people who actually followed Jesus were no longer living. I will have more to say about these so-called Gospels later in this series, but it is enough to notice here that the poor quality of the apocryphal Gospels, those outside the Bible, serves to indirectly confirm the good quality of the biblical Gospels.

If we make a comparison with the works of two trustworthy writers I have already mentioned, Arrian and Plutarch, it will serve to give greater perspective on the relatively short interval between Jesus and the Gospels.

New Testament scholar Craig Blomberg notes that even with later dates for the Gospels than he considers necessary,

“… we are still far closer to the original events than with many ancient biographies. The two earliest biographers of Alexander the Great, for example, Arrian and Plutarch, wrote more than four hundred years after Alexander’s death in 323 B.C., yet historians generally consider them to be trustworthy. Fabulous legends about the life of Alexander did develop over time, but for the most part only during the several centuries after these two writers.” (In J.P. Moreland and Michael Wilkins, Jesus Under Fire, p.29-30)

Another New Testament scholar, Richard Bauckham, also sees the significance of the interval from events to Gospel writing.

“The Gospels were written within the living memory of the events they recount…This is a highly significant fact, entailed not by unusually early datings of the Gospels but by the generally accepted ones.” (Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.7)

“The Gospels were written within the living memory of the events they recount…This is a highly significant fact, entailed not by unusually early datings of the Gospels but by the generally accepted ones.” (Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.7)

“…oral transmission is quite capable of preserving traditions faithfully, even across much longer periods than that between Jesus and the writing of the Gospels…” (Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.240)

So, all of this testimony to the reliability of the oral history and the distinctions that would be made between tales and accounts, together with the relatively short interval in time, tells us that the disciples of Jesus were able to record accurate history concerning the life of Jesus. Those who were closest to Jesus certainly had the ability, and we could even add the motivation, to write about the things concerning their Lord, since they followed Him closely and were immersed in His teaching. After being sent out by Him to spread that teaching, they would have used the conventions of oral history to convey the message until writing became expedient.

The Historicity of the Gospels

How Well Did the Gospel Writers Record History?

Establishing that the Gospel writers had the ability to record history correctly is not the same as establishing that they did. Though they had the right position, opportunity, and motivation, perhaps they were not concerned with accuracy. However, if it could be shown that the authors were concerned with accuracy, and that what they wrote lines up with other historical reference points, it would significantly strengthen the claim that the Gospels are indeed reliable history. Going through all four Gospels for historical references is beyond the scope of this article, so some examples will have to suffice.

The Gospel of John

I think John is a good Gospel to look at first, because it is the one that skeptics have often considered to be the least historically reliable. If the general reliability of this Gospel can be demonstrated, it would implicitly provide additional credibility to the Gospels that have faced fewer challenges. In presenting the following evidence, I do not intend to prove every part of John historically, but by giving a framework that can be found trustworthy, I would hope that the benefit of the doubt could be extended to the parts of the book that have no direct corroborating evidence. In this vein, I agree with Craig Blomberg’s assessment of how historians should be judged.

I think John is a good Gospel to look at first, because it is the one that skeptics have often considered to be the least historically reliable. If the general reliability of this Gospel can be demonstrated, it would implicitly provide additional credibility to the Gospels that have faced fewer challenges. In presenting the following evidence, I do not intend to prove every part of John historically, but by giving a framework that can be found trustworthy, I would hope that the benefit of the doubt could be extended to the parts of the book that have no direct corroborating evidence. In this vein, I agree with Craig Blomberg’s assessment of how historians should be judged.

“A historian who has been found trustworthy where he or she can be tested should be given the benefit of the doubt in cases where no tests are available” (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.63)

One aspect that is easy to overlook, and yet is of significance in historical documents, is the use of names. First of all, we could consider whether the names used in the Gospel even fit the places they are supposed to be from. If they do, we could further consider whether the Gospel writer remembered the names accurately. If we think of the song lyric example, I find song lyrics easier to remember than the names of certain people and I am sure most people have experienced forgetting someone’s name at one time or another. If John got the names right, something difficult to remember, it is very likely that he would be accurate regarding other historical details that would be easier to remember. We might just assume that John would record the right names, but as we will see, it was not a simple task.

According to Richard Bauckham (Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.85, 89) the most popular male names and female names in Palestine from 330BC-200AD were:

- Salome

- Shelamzion

- Martha

- Joanna

Now, those familiar with the Gospels (and Acts) will notice that most of these names can be found in the narratives, and a quick reading of any list of the twelve disciples will reveal that eight of them have names from the male list. Why is this significant? Well, if you were going to make a story up, it would be unlikely that you would get this kind of detail right. We can demonstrate this by applying the same criteria to Egypt, for in descending order of popularity, we get Lazarus, Sabbataius, Joseph, Dositheus, Pappus, Ptolemaius, and Samuel (Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.73). Now, while we do see Lazarus and Joseph again, they appear in a different order, and more significantly, alongside names foreign to the New Testament. Think back to the New Testament now, and observe how the only unfamiliar male name is Manaen and the only unfamiliar female name is Shelamzion (which is even just the longer form of Salome) (Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.74). Also, comparing the proportion of the most popular names in total with those in the Gospels and Acts, there is a remarkable similarity in the percentages of the names used, and we can notice that around half the population had names that were among the most popular (Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, p.71-72).

This is a strong indication that the Gospel writers were familiar with the people that the narratives are purported to have taken place among, but this would be true of Matthew, Mark, and Luke (and Acts) as well, so what is so great about John in this respect? Well, when you have half the population of a relatively small area sharing only a select number of names, you would need to distinguish who is who in other ways than by first name. This could be done in a number of ways, observable in the Gospels and Acts, but what is unique about John is how he does it and with whom.

The first thing to notice about John’s Gospel is a notable omission, and try to follow me, as I will be using the name John to refer to different individuals here. In the other Gospels, the John (not the author of the Gospel) who baptized Jesus is known as “John the Baptist” and “John the son of Zechariah”, but in the Gospel of John, he is only called John (John 1:6, 15, 19). In the other Gospels, they need to distinguish John the son of Zechariah from John the son of Zebedee, but in the Gospel of John, any such identification would be unnecessary, because John the son of Zebedee is not mentioned by name (probably because he is the author of the Gospel) and because John the Baptist’s ministry of baptism is made plain. This shows that the Gospel writer knew what he was talking about and was not just copying the conventional name of this well-known figure.

The first thing to notice about John’s Gospel is a notable omission, and try to follow me, as I will be using the name John to refer to different individuals here. In the other Gospels, the John (not the author of the Gospel) who baptized Jesus is known as “John the Baptist” and “John the son of Zechariah”, but in the Gospel of John, he is only called John (John 1:6, 15, 19). In the other Gospels, they need to distinguish John the son of Zechariah from John the son of Zebedee, but in the Gospel of John, any such identification would be unnecessary, because John the son of Zebedee is not mentioned by name (probably because he is the author of the Gospel) and because John the Baptist’s ministry of baptism is made plain. This shows that the Gospel writer knew what he was talking about and was not just copying the conventional name of this well-known figure.

Another John is mentioned, but only when making another identification; that of Simon, who had the most popular Jewish name for a male (John 1:40-42). What is interesting here is that the other Gospels say that Simon was also called Peter, but only John explains the reference. In this case, John actually interprets two names, Christ (Messiah) and Peter (Cephas). He first gives their Aramaic originals transliterated into Greek and then tells his audience what they mean by giving the Greek version. This is another indication that John is interested in precision, because he explains the events surrounding these individuals, as Messiah and Cephas are the words which would have naturally been used in the actual dialogue.

Another John is mentioned, but only when making another identification; that of Simon, who had the most popular Jewish name for a male (John 1:40-42). What is interesting here is that the other Gospels say that Simon was also called Peter, but only John explains the reference. In this case, John actually interprets two names, Christ (Messiah) and Peter (Cephas). He first gives their Aramaic originals transliterated into Greek and then tells his audience what they mean by giving the Greek version. This is another indication that John is interested in precision, because he explains the events surrounding these individuals, as Messiah and Cephas are the words which would have naturally been used in the actual dialogue.

In dialogue a little further down (John 1:45), Philip describes Jesus as both “of Nazareth” and “the son of Joseph”. While the name Jesus springs one figure to mind for many today, keep in mind that Jesus was number 6 in popularity back then. John records not one, but two, distinguishing characteristics for the One who founded their religion. If this were to be made up much later, no such distinctions would likely be considered, but it fits perfectly in the time in which it is supposed to have been spoken. In fact, the so-called Gospels outside the Bible mostly call Jesus “Christ” or “Saviour”, which fits their later composition.

In dialogue a little further down (John 1:45), Philip describes Jesus as both “of Nazareth” and “the son of Joseph”. While the name Jesus springs one figure to mind for many today, keep in mind that Jesus was number 6 in popularity back then. John records not one, but two, distinguishing characteristics for the One who founded their religion. If this were to be made up much later, no such distinctions would likely be considered, but it fits perfectly in the time in which it is supposed to have been spoken. In fact, the so-called Gospels outside the Bible mostly call Jesus “Christ” or “Saviour”, which fits their later composition.

John also deals with other well-known figures in an interesting way, with one being Lazarus. John 11 tells us of Lazarus, who had sisters named Mary and Martha. The text talks of an amazing miracle, in that Lazarus, after being dead for 4 days, was raised from the dead. Apart from a passing parabolic reference in Luke 16, this is the only place where we find the name Lazarus and the event is not narrated in the other Gospels, as amazing as it was. The single attestation and the miraculous nature of the account have led skeptics to doubt the historicity, but there are indications that speak for the historicity, if the skeptic is willing to listen. First, even though this particular miracle is unique to John, the type of miracle is not (Mark 5:35-43; Luke 7:11-17). Second, there are several unlikely inventions that would seem to emphasize Jesus’ humanity over His divinity, and thus, would not likely be later additions. These would be things like Jesus’ seeming to arrive “late” (11:21, 32), Jesus being troubled (11:33), and Jesus weeping (11:35) (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.169).  Third, Lazarus seems to be in less focus than his sisters, even though he is a male and the subject of the miracle Jesus was about to perform. The village of Bethany is called the village of Mary and Martha. This fits with the sisters being more well-known, because again, the story of Lazarus is not narrated in any other Gospel, but Mary and Martha are talked about in Luke 10:38-42. Fourth, Mary and Martha are among the most popular names for women, just as Lazarus is for men, and inscriptions have even been found near Bethany, connecting all 3 names to that place. However, because of how common the names were, no direct identification can be certain at this point. Fifth, Mary is introduced by connecting her with the account of the anointing of Jesus, which is recorded in Matthew 26:6-13 and Mark 14:3-9. Interestingly, neither Gospel names this woman, even though what she had done was to be known wherever the gospel was preached. John gives this introduction, but he has not yet narrated the event at this point (it appears in his next chapter), so he is counting on people knowing what great act she did, but is simply supplying the added detail of the woman’s name (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.165).

Third, Lazarus seems to be in less focus than his sisters, even though he is a male and the subject of the miracle Jesus was about to perform. The village of Bethany is called the village of Mary and Martha. This fits with the sisters being more well-known, because again, the story of Lazarus is not narrated in any other Gospel, but Mary and Martha are talked about in Luke 10:38-42. Fourth, Mary and Martha are among the most popular names for women, just as Lazarus is for men, and inscriptions have even been found near Bethany, connecting all 3 names to that place. However, because of how common the names were, no direct identification can be certain at this point. Fifth, Mary is introduced by connecting her with the account of the anointing of Jesus, which is recorded in Matthew 26:6-13 and Mark 14:3-9. Interestingly, neither Gospel names this woman, even though what she had done was to be known wherever the gospel was preached. John gives this introduction, but he has not yet narrated the event at this point (it appears in his next chapter), so he is counting on people knowing what great act she did, but is simply supplying the added detail of the woman’s name (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.165).

In John 12:1-8 we have a narrative that is found in Matthew and Mark as well, the anointing of Jesus, but only in John are we told that Judas Iscariot is the one who initiates the complaining about this ointment not being sold and the money given to the poor. Also, only in John are we told the reasoning.  Judas was in charge of the moneybag and he used to steal from it, so he was not actually concerned for the poor, though the other disciples who agreed with him may have been. This detail also explains why none of the disciples thought it was strange that Judas left their company in the middle of a very solemn moment. Jesus said for Judas to do what he was going to do quickly and the disciples thought that meant to use the moneybag to either buy something or give to the poor (John 13:21-30).

Judas was in charge of the moneybag and he used to steal from it, so he was not actually concerned for the poor, though the other disciples who agreed with him may have been. This detail also explains why none of the disciples thought it was strange that Judas left their company in the middle of a very solemn moment. Jesus said for Judas to do what he was going to do quickly and the disciples thought that meant to use the moneybag to either buy something or give to the poor (John 13:21-30).

In John 14:22 we find the name Judas again, which would need further identification for obvious reasons, being both generally popular and specifically used just recently in John. In an odd description, John does not provide information about who Judas is, but who he is not. John knows that the much more well-known Judas is the son of Simon Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus (13:2, 26). He also knows that there are only 2 men named Judas in Jesus’ group of followers, even though Jesus also had a brother named Judas and it was a popular name. This again shows familiarity with the original situation, enough to identify the Judas that was speaking by saying he was not the other Judas, who had already gone out from the group (John 13:30) and had been a major character in the previous passage.

Finally, just as Mary was identified as the one who anointed Jesus from other Gospel narratives, Simon Peter makes a revealing appearance in John that stood anonymous in the other Gospels. All 4 Gospels record that one of Jesus’ followers cut off the ear of the high priest’s servant with a sword, but only John tells us that it was Simon Peter who did this (John 18:10). John is also the only one to tell us that the name of that servant was Malchus.

Finally, just as Mary was identified as the one who anointed Jesus from other Gospel narratives, Simon Peter makes a revealing appearance in John that stood anonymous in the other Gospels. All 4 Gospels record that one of Jesus’ followers cut off the ear of the high priest’s servant with a sword, but only John tells us that it was Simon Peter who did this (John 18:10). John is also the only one to tell us that the name of that servant was Malchus.

Now, I am not saying that any of these are of major significance in isolation, but they do give the picture that John is concerned with historical accuracy. Many more details could be noted, but suffice it to say that John shows considerable attention to historical factors. Norman Geisler and Frank Turek list 59 details of John’s Gospel that are either historically confirmed or historically probable (I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist, p.263-268).

Now, I am not saying that any of these are of major significance in isolation, but they do give the picture that John is concerned with historical accuracy. Many more details could be noted, but suffice it to say that John shows considerable attention to historical factors. Norman Geisler and Frank Turek list 59 details of John’s Gospel that are either historically confirmed or historically probable (I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist, p.263-268).  Those that are historically confirmed have some other trusted source that lines up with what John says. One quick example would be the 5 roofed colonnades at the pool of Bethesda (John 5:2) being confirmed by archaeological and literary sources (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.109).

Those that are historically confirmed have some other trusted source that lines up with what John says. One quick example would be the 5 roofed colonnades at the pool of Bethesda (John 5:2) being confirmed by archaeological and literary sources (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.109).  Those that are historically probable are details that are very unlikely to have been made up for various reasons. A quick example of this would be the fact that Joseph of Arimathea buried Jesus. It would be embarrassing to admit that a peripheral figure and not Jesus’ disciples buried Him, and it would be easy to refute if not true, because Joseph was a member of the Jewish council and would thus be well-known. For these and other reasons, most scholars accept the authenticity of this account (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.256). Craig Blomberg even puts the Gospel of John above the other Gospels (the Synoptics) in certain respects.

Those that are historically probable are details that are very unlikely to have been made up for various reasons. A quick example of this would be the fact that Joseph of Arimathea buried Jesus. It would be embarrassing to admit that a peripheral figure and not Jesus’ disciples buried Him, and it would be easy to refute if not true, because Joseph was a member of the Jewish council and would thus be well-known. For these and other reasons, most scholars accept the authenticity of this account (Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel, p.256). Craig Blomberg even puts the Gospel of John above the other Gospels (the Synoptics) in certain respects.

“Another interesting feature of John is that, when compared with the Synoptics, his Gospel consistently gives more references to chronology, geography, topography, and the like.” (In J.P. Moreland and Michael Wilkins, Jesus Under Fire, p.39)

Blomberg goes on to say that this is all the more significant, because John does not seem to be making any point with it and it seems to appear incidentally. John is not trying to convince us that he knows what he is talking about, but he simply reflects that he does through his natural narration of the events in Jesus’ life. So, since John’s Gospel turns out to be a lot more accurate than many skeptics give it credit for, further confidence can also be placed in the Gospels in which there was already a greater level of confidence than in John.

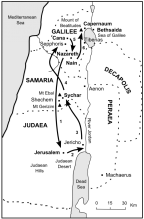

Acts and the Gospel of Luke

It is of interest to investigate both the book of Acts and the Gospel of Luke, though not much detail will be necessary, since this history happens to be the one that skeptics are least skeptical about, as opposed to John’s Gospel. One reason the books should both be considered together is that they are similar to a two volume set, both addressed to the same person (Luke 1:3; Acts 1:1), with the second book making reference to the first.  Another reason would be that the Gospel deals with one corner of the Roman Empire, while Acts narrates events over much more of it. So with Acts there are potentially more details that could be historically examined through what we know of the Roman Empire. In fact, one of the greatest archaeologists in history, Sir William Ramsay, thought that it would be easy to show that Luke’s history in Acts was incorrect, because he mentioned so many details. However, having examined the evidence himself, he was forced to completely reverse his earlier skepticism.

Another reason would be that the Gospel deals with one corner of the Roman Empire, while Acts narrates events over much more of it. So with Acts there are potentially more details that could be historically examined through what we know of the Roman Empire. In fact, one of the greatest archaeologists in history, Sir William Ramsay, thought that it would be easy to show that Luke’s history in Acts was incorrect, because he mentioned so many details. However, having examined the evidence himself, he was forced to completely reverse his earlier skepticism.

“I may fairly claim to have entered on this investigation without any prejudice in favour of the conclusion which I shall now attempt to justify to the reader. On the contrary, I began with a mind unfavourable to it, for the ingenuity and apparent completeness of the Tübingen theory had at one time quite convinced me. It did not lie then in my line of life to investigate the subject minutely; but more recently I found myself often brought in contact with the book of Acts as an authority for the topography, antiquities, and society of Asia Minor. It was gradually borne in upon me that in various details the narrative showed marvellous truth. In fact, beginning with the fixed idea that the work was essentially a second-century composition, and never relying on its evidence as trustworthy for first-century conditions, I gradually came to find it a useful ally in some obscure and difficult investigations. ” (William Ramsay, Saint Paul the Traveler and Roman Citizen, p.12)

Josh McDowell quotes Ramsay in having said that Luke “should be placed along with the very greatest of historians.” (The New Evidence that Demands a Verdict, p.63). McDowell then quotes already noted historian A.N. Sherwin-White in confirmation of this assertion as well.

“For Acts the confirmation of his historicity is overwhelming…Any attempt to reject its basic historicity must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted.” (The New Evidence that Demands a Verdict, p.64)

Another Roman historian, Colin Hemer, went through the last 16 chapters of the book of Acts (which records the major travels of Paul through the Roman Empire) and noted 84 facts confirmed by historical and archaeological research (The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic Culture, p.108-158). Since it took Hemer 50 pages, I will not attempt to give all the details, but an example will illustrate Luke’s accuracy. The leaders of different places and different responsibilities had different names, and Luke is very accurate in this regard, as he mentions these different titles correctly for any given place and position.

Another Roman historian, Colin Hemer, went through the last 16 chapters of the book of Acts (which records the major travels of Paul through the Roman Empire) and noted 84 facts confirmed by historical and archaeological research (The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic Culture, p.108-158). Since it took Hemer 50 pages, I will not attempt to give all the details, but an example will illustrate Luke’s accuracy. The leaders of different places and different responsibilities had different names, and Luke is very accurate in this regard, as he mentions these different titles correctly for any given place and position.  On Cyprus, the governor is called proconsul (ἀνθύπατος) (Acts 13:7). In Philippi Luke describes magistrates (στρατηγοί) (Acts 16:20, 22). Those in Thessalonica are called authorities (πολιτάρχαι) (Acts 17:6, 8). In Ephesus we hear of the town clerk (γραμματεὺς) (Acts 19:35). The leader on Malta is called the chief man (πρώτος) (Acts 28:7). This may seem simple, but someone writing about these people and places could very easily use a more general name and thereby make a mistake. This would stand in contrast to Luke, who exhibits remarkable familiarity with the history he describes and makes no mistake in his narrative. Other examples involve details of geography, language, religion, and society, but suffice it to say that Luke knew what he was talking about and recorded accurate history.

On Cyprus, the governor is called proconsul (ἀνθύπατος) (Acts 13:7). In Philippi Luke describes magistrates (στρατηγοί) (Acts 16:20, 22). Those in Thessalonica are called authorities (πολιτάρχαι) (Acts 17:6, 8). In Ephesus we hear of the town clerk (γραμματεὺς) (Acts 19:35). The leader on Malta is called the chief man (πρώτος) (Acts 28:7). This may seem simple, but someone writing about these people and places could very easily use a more general name and thereby make a mistake. This would stand in contrast to Luke, who exhibits remarkable familiarity with the history he describes and makes no mistake in his narrative. Other examples involve details of geography, language, religion, and society, but suffice it to say that Luke knew what he was talking about and recorded accurate history.

What does this say about Luke’s Gospel, then? Well, I believe we should remember the quote from Craig Blomberg above. We should give a historian the benefit of the doubt where they cannot be tested when this historian has proven trustworthy where they can be tested. When we read Luke, we can keep in mind that this is the author of Acts, so if he paid such attention to accuracy in the latter book, his quality as a historian should also be connected with the former book. You do not simply need to take my word for it, though, since Luke himself tells us of his attention to detail.

What does this say about Luke’s Gospel, then? Well, I believe we should remember the quote from Craig Blomberg above. We should give a historian the benefit of the doubt where they cannot be tested when this historian has proven trustworthy where they can be tested. When we read Luke, we can keep in mind that this is the author of Acts, so if he paid such attention to accuracy in the latter book, his quality as a historian should also be connected with the former book. You do not simply need to take my word for it, though, since Luke himself tells us of his attention to detail.

“Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught.” (Luke 1:1-4 ESV)

This introduction to Luke’s Gospel does not in itself guarantee that everything he writes is correct, but it does give the impression that this is Luke’s intention and that he did the research to make sure that Theophilus could have confidence that the account was accurate.  To see this demonstrated, one need only turn to the beginning of Luke 3, where not 1, but 6 historical reference points are given for the start of John the Baptist’s ministry in the span of 2 verses (Tiberius was Caesar, Pontius Pilate was the governor, Herod, Philip, and Lysanias were tetrachs, Annas and Caiaphas were high priests). However, some have still claimed that Luke did not live up to his introduction, but just as historical information has confirmed Acts, the same has been true of Luke. There will always be skeptics, so even though Luke is considered generally reliable, it may be instructive to consider a charge of inaccuracy to see how the Gospel holds up.

To see this demonstrated, one need only turn to the beginning of Luke 3, where not 1, but 6 historical reference points are given for the start of John the Baptist’s ministry in the span of 2 verses (Tiberius was Caesar, Pontius Pilate was the governor, Herod, Philip, and Lysanias were tetrachs, Annas and Caiaphas were high priests). However, some have still claimed that Luke did not live up to his introduction, but just as historical information has confirmed Acts, the same has been true of Luke. There will always be skeptics, so even though Luke is considered generally reliable, it may be instructive to consider a charge of inaccuracy to see how the Gospel holds up.

A commonly cited example is the census described in Luke 2:1-5, for which some evidence suggested that Luke got his facts wrong.

Richard Dawkins uses this example to refute the reliability of the Bible (The God Delusion, p.119), making fun of the idea of returning to an ancestral city for a census and accusing Luke of carelessness in “mentioning events that historians are capable of independently checking.” I use Dawkins as an example because of his popularity among skeptics, but I must say that he does base his objections on the work of historical scholars. To spell it out, the problems presented by this passage are that Augustus called for the census of all the people, that people had to return to their ancestral city, and that Quirinius was the governor at the time.

To consider Augustus calling for the census, there was no evidence that he registered the whole Roman Empire at the same time. However, it is an assumption to claim that Augustus would have to register all at the same time and Luke does not say that, but merely that they “should be registered” (ESV). In light of this, evidence has been found that these events happened regularly around the Roman Empire, starting in the very reign under question, the reign of Augustus. In fact, it took place about every 14 years. Furthermore, an Egyptian papyrus describes the practice of returning to one’s ancestral city.  Finally, the issue with Quirinius is that we know he was made governor of Syria by Augustus in 6AD and that a census took place around this time in Syria and Judea, but the birth of Christ is placed around 6BC. The interesting thing is that Sir William Ramsay comes in to correct Dawkins and others who thought the same way Ramsay did before examining the evidence; namely, that Luke was foolish to mention historical events that could be checked. As it turns out, Ramsay discovered several inscriptions indicating that Quirinius was governor of Syria twice, once before the time in 6AD that I already mentioned around 7BC. So, if one census occurred no earlier than 6AD, the average timing would place the previous census within an adequate timeframe to send Jesus’ parents to their ancestral city of Bethlehem for Jesus’ birth while Quirinius was governor the first time. We have even further reason to believe that Luke knew what he was talking about, because he makes a reference to the later census in Acts 5:37. It seems that he knew of two and distinguishes one from the other in his Gospel. Looking back to Luke 2, possible translations of the verse in question are “This was the first registration when Quirinius was governor of Syria” and “This was the registration before Quirinius was governor of Syria”. So however it is translated, history has a satisfactory answer (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.172-173; Josh McDowell, The New Evidence that Demands a Verdict, p.63-64).

Finally, the issue with Quirinius is that we know he was made governor of Syria by Augustus in 6AD and that a census took place around this time in Syria and Judea, but the birth of Christ is placed around 6BC. The interesting thing is that Sir William Ramsay comes in to correct Dawkins and others who thought the same way Ramsay did before examining the evidence; namely, that Luke was foolish to mention historical events that could be checked. As it turns out, Ramsay discovered several inscriptions indicating that Quirinius was governor of Syria twice, once before the time in 6AD that I already mentioned around 7BC. So, if one census occurred no earlier than 6AD, the average timing would place the previous census within an adequate timeframe to send Jesus’ parents to their ancestral city of Bethlehem for Jesus’ birth while Quirinius was governor the first time. We have even further reason to believe that Luke knew what he was talking about, because he makes a reference to the later census in Acts 5:37. It seems that he knew of two and distinguishes one from the other in his Gospel. Looking back to Luke 2, possible translations of the verse in question are “This was the first registration when Quirinius was governor of Syria” and “This was the registration before Quirinius was governor of Syria”. So however it is translated, history has a satisfactory answer (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.172-173; Josh McDowell, The New Evidence that Demands a Verdict, p.63-64).

So, having looked at the Gospel generally thought to be the least reliable and then the Gospel considered to be the most reliable, I believe we can observe a pattern. General skepticism does not hold up upon closer scrutiny and the Gospel writers demonstrate attention to accurate detail, even in matters that might initially seem to be of little consequence. Therefore, I suggest that since the Gospels have been historically tested and been confirmed in certain areas, that we should extend a strong vote of confidence to the portions of the Gospel that are thus far untestable.

The Internal Consistency of the Gospels

How Well Do the Gospels Line Up with Each Other?

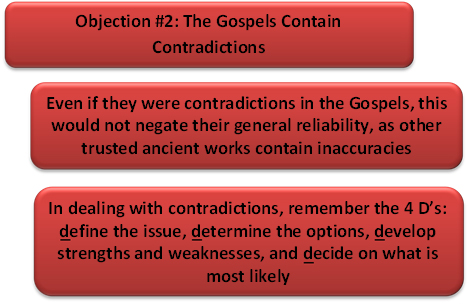

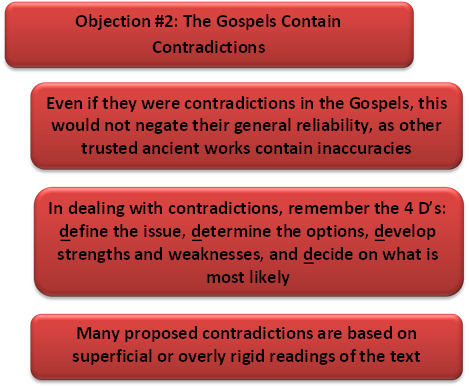

I have often heard people talk about apparent contradictions in the Gospels, and ask how, if one Gospel says one thing about an event and a second Gospel says another, are we to know which Gospel to believe, if any? This is important to ask and is a common objection, so I will certainly address this in the objections article that will accompany this article. After all, even if the disciples were able to record accurate history and even gave many historical indications that they did this, having various contradictions between them would undermine the historicity in the minds of many. Though I will address contradictions, as I have said, what I have not often heard is how well the Gospels fit together. Amidst all this talk of how the Gospels might disagree, I would like to present evidence of their remarkable agreement. I hope this will also provide a foundation from which to assess alleged contradictions.

The way I plan to do this is through the evidence of what have been called “undesigned coincidences”, which I have based on the work of 19th century scholar John James Blunt (Undesigned Coincidences in the Writings Both of the Old and New Testament). More recently, his work has been revived by philosopher Timothy McGrew, specifically regarding the Gospels.  An undesigned coincidence is basically a feature of a narrative where an event(s) is more fully explained in another narrative. Though undesigned coincidences appear throughout the Bible, I believe they are most evident in the Gospels, because there are 4 of them and some of the same events are narrated more regularly than in other portions of the Bible. If you do not understand what I mean, examples are usually the best way to clear that up, but hopefully explaining the name will give a little more clarity. These features are called “undesigned” because they would be very difficult to explain if they were planned and they are called “coincidences” because they connect narratives together, though incidentally. In other words, there may be no obvious intention, and yet the Gospels line up with each other in extraordinary ways, like pieces of a puzzle.

An undesigned coincidence is basically a feature of a narrative where an event(s) is more fully explained in another narrative. Though undesigned coincidences appear throughout the Bible, I believe they are most evident in the Gospels, because there are 4 of them and some of the same events are narrated more regularly than in other portions of the Bible. If you do not understand what I mean, examples are usually the best way to clear that up, but hopefully explaining the name will give a little more clarity. These features are called “undesigned” because they would be very difficult to explain if they were planned and they are called “coincidences” because they connect narratives together, though incidentally. In other words, there may be no obvious intention, and yet the Gospels line up with each other in extraordinary ways, like pieces of a puzzle.

I have read the Gospels many times, and in a way, that can work against me in noticing the confirming details that are there to be found. I never really thought about undesigned coincidences before they were pointed out to me. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but I was just hindered from seeing a different perspective by my familiarity with the Gospels. So, whether you have read the Gospels 30 times or none, I plan to help you see something that is likely new to you. I can say that, because last year I taught this in Stockholm to a group of 30 people of all different ages and not one of them had heard anything like it before. A major reason many do not think of these features is because we do not often think of the uniqueness of each Gospel, but lump them all together into one big Gospel with all the events. However, when we appreciate each Gospel individually, and then compare them very intentionally, some interesting observations arise.

I have read the Gospels many times, and in a way, that can work against me in noticing the confirming details that are there to be found. I never really thought about undesigned coincidences before they were pointed out to me. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but I was just hindered from seeing a different perspective by my familiarity with the Gospels. So, whether you have read the Gospels 30 times or none, I plan to help you see something that is likely new to you. I can say that, because last year I taught this in Stockholm to a group of 30 people of all different ages and not one of them had heard anything like it before. A major reason many do not think of these features is because we do not often think of the uniqueness of each Gospel, but lump them all together into one big Gospel with all the events. However, when we appreciate each Gospel individually, and then compare them very intentionally, some interesting observations arise.

Just One Thing

Sometimes the events narrated in different Gospels will be nearly identical, but 1 Gospel will have a single detail not found elsewhere. This is not strange, because rarely do different people telling the same story agree exactly, but it is significant when this little detail explains something puzzling about the other account.

Matthew 26:67-68 describes how the council that condemned Jesus to death started to strike Him after they gave the sentence. Have you ever asked yourself why they tell Jesus to prophesy who struck Him? After all, could He not simply look and then say who had struck Him, without using His prophetic abilities? Well, you might be tempted to just forget about it or to offer some extravagant interpretation…or you could just look at the same event narrated in Luke 22:63-64. Luke gives us the tiny little detail that puts the pieces of the puzzle together; namely, that they blindfolded Jesus for this. That is why He would be forced to prophesy to identify who struck Him, because He could not actually see at the time. In this way, Luke explains Matthew.

Matthew 26:67-68 describes how the council that condemned Jesus to death started to strike Him after they gave the sentence. Have you ever asked yourself why they tell Jesus to prophesy who struck Him? After all, could He not simply look and then say who had struck Him, without using His prophetic abilities? Well, you might be tempted to just forget about it or to offer some extravagant interpretation…or you could just look at the same event narrated in Luke 22:63-64. Luke gives us the tiny little detail that puts the pieces of the puzzle together; namely, that they blindfolded Jesus for this. That is why He would be forced to prophesy to identify who struck Him, because He could not actually see at the time. In this way, Luke explains Matthew.

Luke 9:29-36 describes the transfiguration of Jesus, including Jesus’ altered appearance, Moses and Elijah talking with Him, and a voice from the clouds saying to listen to Him. It is safe to say that this would have been an amazing experience for the 3 disciples who were there. However, Luke tells us that they told nothing of what they had seen to anyone in those days. If that seems a little odd to you, you are not alone. Why would they not tell anyone? We need look no further than the same event in Mark 9:2-10. As it turns out, Mark records how Jesus commanded the disciples to tell no one until after His resurrection. This explains both why they did not proclaim it initially and why they eventually did proclaim it, based on Jesus’ instruction. In this way, Mark explains Luke.

Luke 9:29-36 describes the transfiguration of Jesus, including Jesus’ altered appearance, Moses and Elijah talking with Him, and a voice from the clouds saying to listen to Him. It is safe to say that this would have been an amazing experience for the 3 disciples who were there. However, Luke tells us that they told nothing of what they had seen to anyone in those days. If that seems a little odd to you, you are not alone. Why would they not tell anyone? We need look no further than the same event in Mark 9:2-10. As it turns out, Mark records how Jesus commanded the disciples to tell no one until after His resurrection. This explains both why they did not proclaim it initially and why they eventually did proclaim it, based on Jesus’ instruction. In this way, Mark explains Luke.

Matthew 26:20-25 records Jesus revealing to His disciples that one of them would betray Him, and Judas, the one who was going to betray Him, asked Jesus directly if it was him that would commit the betrayal. Jesus responds “You have said so” (ESV), but there is no reaction recorded from the disciples. Why would no one say anything after such a serious accusation? John 13:21-30 tells us that, even though some of this conversation was public, the actual identification of Judas as the betrayer was not perceived by the majority of the disciples. In this way, John explains Matthew.

Matthew 26:20-25 records Jesus revealing to His disciples that one of them would betray Him, and Judas, the one who was going to betray Him, asked Jesus directly if it was him that would commit the betrayal. Jesus responds “You have said so” (ESV), but there is no reaction recorded from the disciples. Why would no one say anything after such a serious accusation? John 13:21-30 tells us that, even though some of this conversation was public, the actual identification of Judas as the betrayer was not perceived by the majority of the disciples. In this way, John explains Matthew.

Mark 9:11-13 contains a description of Elijah, how he had already come and that “they” did to him whatever they pleased. The disciples bring up the question and Jesus gives an answer, but it is not at all made clear what they are talking about. Who is this Elijah and why does it matter?  The parallel passage in Matthew 17:11-13 gives us a better idea. Matthew includes the fact that the disciples understood that Jesus was referring to John the Baptist, and since he had been imprisoned and eventually executed (Matthew 11:2, 14:1-12), Jesus was using this description to point to His own imminent suffering and death. In this way, Matthew explains Mark.

The parallel passage in Matthew 17:11-13 gives us a better idea. Matthew includes the fact that the disciples understood that Jesus was referring to John the Baptist, and since he had been imprisoned and eventually executed (Matthew 11:2, 14:1-12), Jesus was using this description to point to His own imminent suffering and death. In this way, Matthew explains Mark.

Mentioned in Passing

These undesigned coincidences are often subtle or mentioned in passing. These would be details that are not necessarily linked to major points, which also makes them easy to miss. However, if we think about them in terms of historical value, they have added significance, because they reflect that the author sees the historical picture and records the detail, even if it is not directly important for his message.

Luke 5:27-28 introduces us to a tax collector named Levi. Jesus calls him to follow and it says “leaving everything, he rose and followed him” (ESV), which sounds a lot like the calling of Peter, James, and John a little earlier (Luke 5:11). This has every appearance of the calling of an important disciple, but oddly enough, we hear nothing else about this Levi. Luke 6:14-16 records the names of the 12 disciples, but Levi is nowhere to be found. Why would Luke include this specific calling if he played no further part in Luke’s Gospel?  For those more familiar with the Gospels, you might have been thinking that Luke 6:15 does mention that one of the disciples was named Matthew and that Matthew was a tax collector. This is the answer, of course, but it illustrates how easily we can gloss over the fact that Luke does not give us all the information we need to work that out, so it would be easy to miss that detail. Matthew 9:9 gives the same narrative as in Luke 5, but the name given is Matthew, which is the more well-known name of the tax collector who left everything to become a disciple of Jesus. Matthew’s list of the 12 disciples includes Matthew and adds that he was a tax collector (Matthew 10:2-4). The name change may have been something that Jesus Himself initiated, as He did with other disciples, or it may have Matthew’s own decision. Whatever the case, the Gospel traditionally ascribed to Matthew is the only one that connects the tax collector and the disciple, so even if we have it in our minds that Matthew was a tax collector, we have to remember that only Matthew’s Gospel tells us that. In this way, Matthew explains Luke.

For those more familiar with the Gospels, you might have been thinking that Luke 6:15 does mention that one of the disciples was named Matthew and that Matthew was a tax collector. This is the answer, of course, but it illustrates how easily we can gloss over the fact that Luke does not give us all the information we need to work that out, so it would be easy to miss that detail. Matthew 9:9 gives the same narrative as in Luke 5, but the name given is Matthew, which is the more well-known name of the tax collector who left everything to become a disciple of Jesus. Matthew’s list of the 12 disciples includes Matthew and adds that he was a tax collector (Matthew 10:2-4). The name change may have been something that Jesus Himself initiated, as He did with other disciples, or it may have Matthew’s own decision. Whatever the case, the Gospel traditionally ascribed to Matthew is the only one that connects the tax collector and the disciple, so even if we have it in our minds that Matthew was a tax collector, we have to remember that only Matthew’s Gospel tells us that. In this way, Matthew explains Luke.

John 3:24 and 6:67 include references to details that John mentions briefly, but never takes the time to explain or narrate. The first verse says that John the Baptist had not yet been put in prison and the second verse mentions Jesus saying something to the Twelve. This might not seem odd to you, but the fact is that John the Baptist’s arrest is not described anywhere else in the book, nor is any identification given for the Twelve.  On one side, why would John make a chronological reference to an event he does not narrate later? On another side, why would he make a biographical reference to a group he has not introduced before? Mark 6:17 describes that John the Baptist was indeed arrested and Mark 3:13-19 does include a list of names for John’s mystery group. Now, what is helpful to understand is that John is very widely held to have been written after Mark. So it would make sense that John would not have to narrate John the Baptist’s imprisonment or tell his audience the identity of the Twelve, because it would already have become known through Mark and the other Gospels. John mentions historical persons and events in passing, confirming their veracity, though without actually making a big deal of it. Mark fills in the details, but John is content with what is more relevant to his Gospel in particular. In this way, Mark explains John.

On one side, why would John make a chronological reference to an event he does not narrate later? On another side, why would he make a biographical reference to a group he has not introduced before? Mark 6:17 describes that John the Baptist was indeed arrested and Mark 3:13-19 does include a list of names for John’s mystery group. Now, what is helpful to understand is that John is very widely held to have been written after Mark. So it would make sense that John would not have to narrate John the Baptist’s imprisonment or tell his audience the identity of the Twelve, because it would already have become known through Mark and the other Gospels. John mentions historical persons and events in passing, confirming their veracity, though without actually making a big deal of it. Mark fills in the details, but John is content with what is more relevant to his Gospel in particular. In this way, Mark explains John.

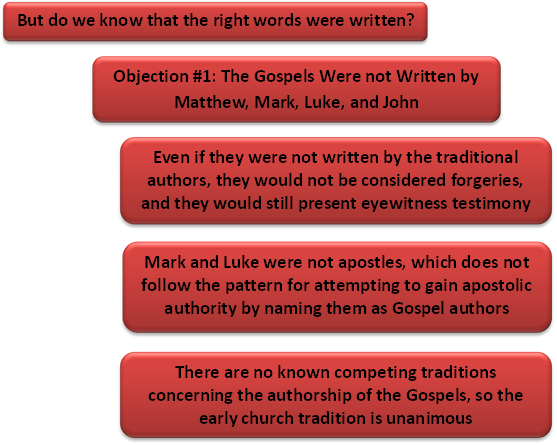

John 21:1-3 describes Peter, the sons of Zebedee, and some other disciples deciding to go fishing at Peter’s initiative, after Jesus had revealed Himself to His disciples.  Why would they go fishing? The answer is quite simple to those familiar with the Gospels. Peter and the sons of Zebedee were fishermen before Jesus called them to be His disciples. However, I am sure by now that it will surprise no one, based on the evidence I have already presented, that John does not in fact divulge this information anywhere in his Gospel. This is another illustration of how we can form a conglomerate picture of the Gospels, forgetting what each Gospel includes or omits. If we go to Matthew 4:18-22, though, we see James and John, sons of Zebedee, in addition to Peter, leaving their fishing nets to follow Jesus. In this way, Matthew explains John.