By Matt Lefebvre

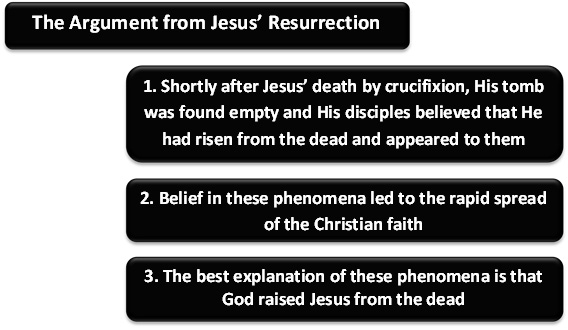

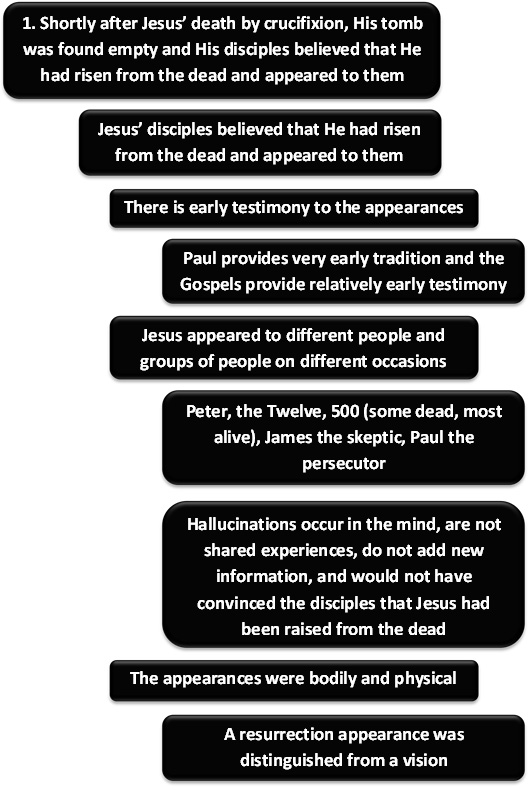

This post is a continuation of the argument from Jesus’ resurrection. Please see Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 if you have not read them yet.

To read along with audio for this article, click here Resurrection-Part4

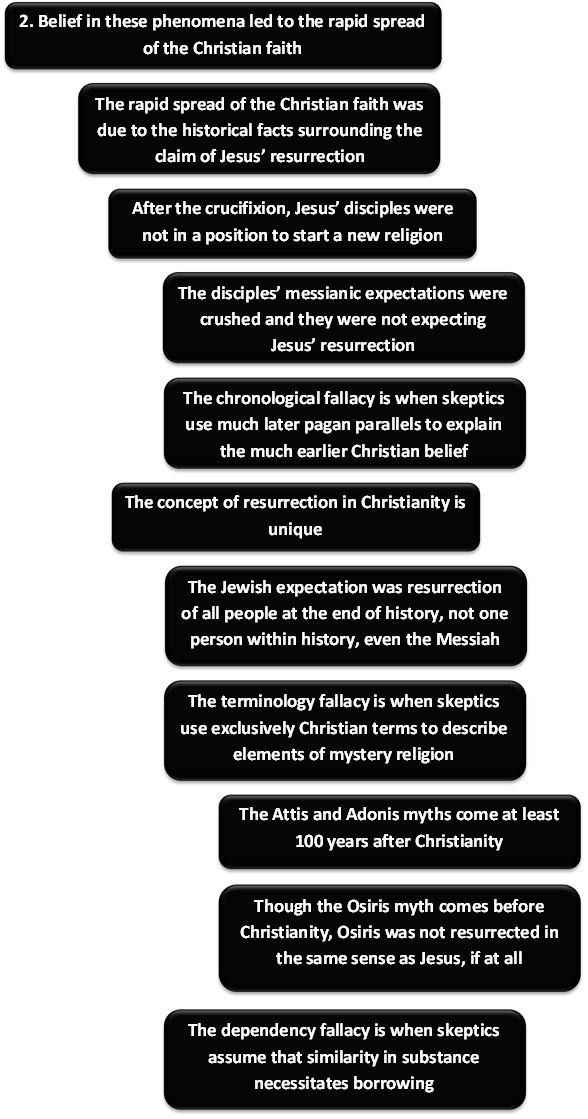

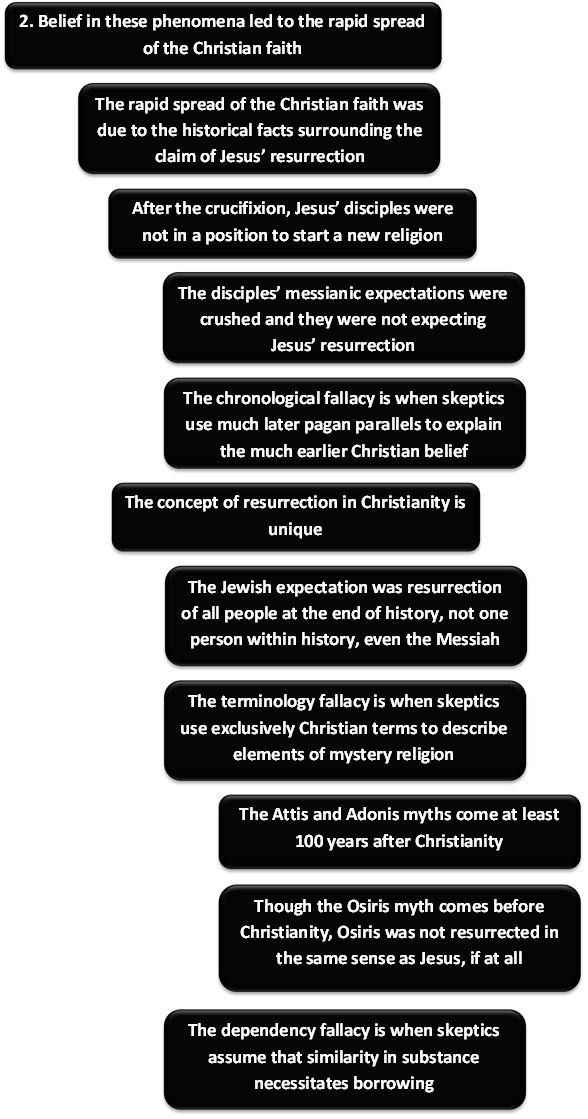

2. Belief in these phenomena led to the rapid spread of the Christian faith

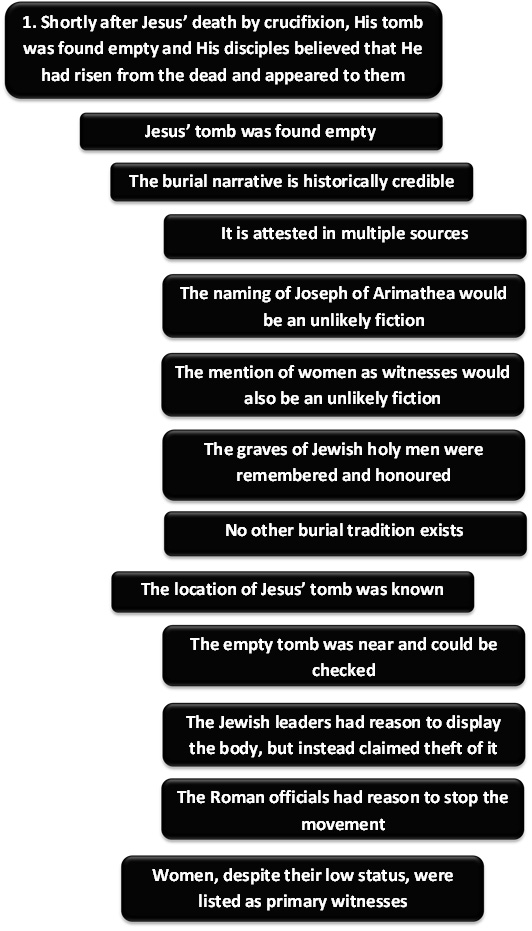

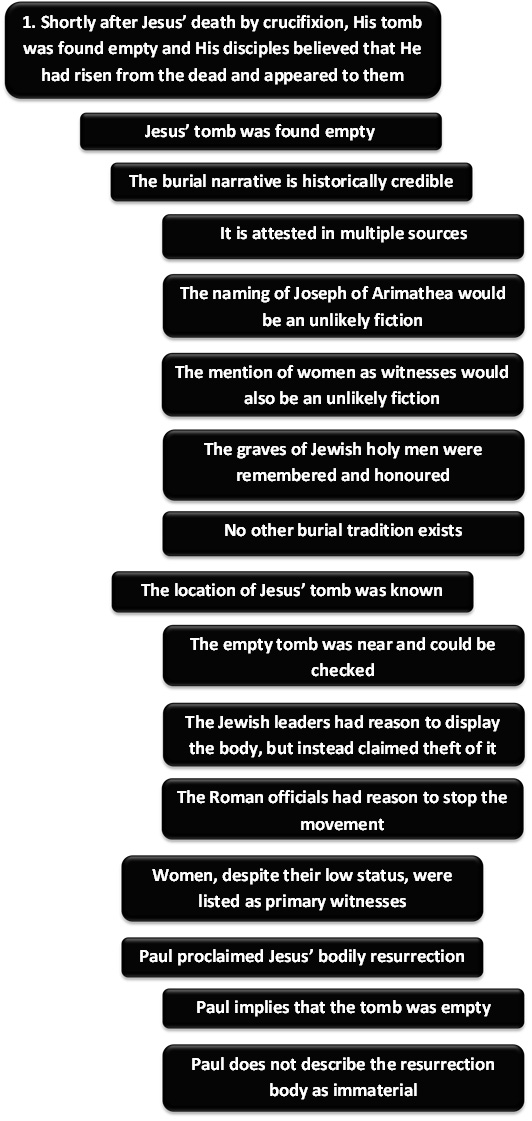

In discussing the above facts surrounding the resurrection of Jesus, including select objections, I found myself using the words “even if” a lot. What I mean by that is in considering these facts, it becomes clear that they are not only widely held for good reason, but also that there is significant difficulty involved in explaining them away. In finding any particular naturalistic hypothesis wanting in regard to explaining just one of these facts, it is quite incredible to suggest that all the facts may be explained by such a hypothesis. Though I believe that Jesus’ death by crucifixion, the subsequent emptiness of the tomb in which He was buried, and the belief of His disciples that He had appeared to them resurrected are sufficient to make a strong case for the resurrection of Jesus as the best explanation, I also believe that there is one more historical consideration worth discussing.  In spite of the strength of the historical evidence for what I have described above, there are still those who would seek to sweep all of it under the rug by suggesting that Christianity just copied other existing beliefs of the Greco-Roman world. Such critics would grant that the Christian faith spread rapidly in the Roman Empire and that this requires historical explanation, but they would deny that it was the result of Jesus being raised from the dead. In its place, they would point to parallels with other ancient beliefs among Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans concerning dying and rising gods. Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy question the validity of ignoring such parallels.

In spite of the strength of the historical evidence for what I have described above, there are still those who would seek to sweep all of it under the rug by suggesting that Christianity just copied other existing beliefs of the Greco-Roman world. Such critics would grant that the Christian faith spread rapidly in the Roman Empire and that this requires historical explanation, but they would deny that it was the result of Jesus being raised from the dead. In its place, they would point to parallels with other ancient beliefs among Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans concerning dying and rising gods. Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy question the validity of ignoring such parallels.

“Why should we consider the stories of Osiris, Dionysius, Adonis, Attis, Mithras, and the other Pagan Mystery saviors as fables, yet come across essentially the same story told in a Jewish context and believe it to be the biography of a carpenter from Bethlehem?” (The Jesus Mysteries, p.9).

“Why should we consider the stories of Osiris, Dionysius, Adonis, Attis, Mithras, and the other Pagan Mystery saviors as fables, yet come across essentially the same story told in a Jewish context and believe it to be the biography of a carpenter from Bethlehem?” (The Jesus Mysteries, p.9).

“The traditional history of Christianity cannot convincingly explain why the Jesus story is so similar to ancient Pagan myths.” (The Laughing Jesus, p.61).

According to this understanding, Christianity was nothing new, but simply a rehashing of common beliefs already in existence, something also found in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (p.232). Now, while I consider this opinion to ignore much more historical evidence than the alternate hypotheses mentioned above, in the interest of pursuing the “even if” of naturalistic explanations, I will examine the origin of the Christian faith to see how this popular (yet ill-founded in my opinion) belief fares.

While many scholars from various theological and philosophical perspectives can agree on basic historical bedrock concerning the beginning of Christianity, it is in explaining the phenomena where those from different sides of the philosophical spectrum begin to part ways. I find it interesting that there could be so much unanimity concerning the basic facts and equally as much diversity concerning the interpretation. Indeed, the scholars I refer to have read each other’s work and some of them have even debated over the interpretation of the facts, so in the case of many, it is not lack of exposure to opposing views that leads to their confidence in their own position. As pointed out above, presuppositions have a lot to do with how the evidence is read. To look at the New Testament witness to Jesus being raised from the dead can seem utterly unacceptable to those who presuppose that dead men cannot rise from the dead, and conversely, completely consistent with a Christian view of the world; namely, that God can raise the dead. It is at this point that some might despair, some might agree to disagree, and some might demand that the other adopt their presuppositions. I suggest a slightly different route, agreeing that presuppositions need to change if they do not correspond to reality, while also recognizing that this is not an easy thing to do. I would certainly hope that the evidence I am presenting will convince many who were previously skeptical that Jesus really did rise from the dead. However, I am not so naïve as to think that everyone will agree with my conclusions, even if they join the majority of critical scholars in at least granting the minimal facts.  This is not something that I feel is detrimental to the case for the historicity of the resurrection, and in fact, I consider it to be something that attests to what I am about to discuss. That deeply held beliefs are difficult to change is significant when considering the origin of the Christian faith. In thinking about what might have caused the radical transformation in the disciples of Jesus, we will see how good an explanation it is to postulate that Christians simply presented old beliefs in a new light. There are at least four good reasons to believe that the Christian faith spread rapidly based on the above mentioned historical facts.

This is not something that I feel is detrimental to the case for the historicity of the resurrection, and in fact, I consider it to be something that attests to what I am about to discuss. That deeply held beliefs are difficult to change is significant when considering the origin of the Christian faith. In thinking about what might have caused the radical transformation in the disciples of Jesus, we will see how good an explanation it is to postulate that Christians simply presented old beliefs in a new light. There are at least four good reasons to believe that the Christian faith spread rapidly based on the above mentioned historical facts.

1. The situation of the disciples did not lend itself toward the making of a new religion. In discussing the origin of the Christian faith, it is significant to think about the obstacles that had to be overcome for anything to get going, and specific to our investigation, how this could possibly be explained by appeal to parallels in other religious traditions. As I pointed out in the discussion of the first fact presented in this article, Jesus died by crucifixion, as attested by both Christian and non-Christian sources from the ancient Roman Empire. That being the case, any treatment of what happened with the disciples subsequently must include the effects of this. First, according to William Lane Craig, “It is difficult to exaggerate what a devastating effect the crucifixion must have had on the disciples. They had no conception of a dying, much less a rising, Messiah, for the Messiah would reign forever (cf. John 12:34).” (In Jesus Under Fire, p.159). Whatever you might think about whether Jesus actually was the Messiah or not, His disciples certainly believed that He was, but to think that His sudden death by crucifixion would leave that belief unaltered is to misunderstand almost everything that was expected of the Messiah. Though there was not total consensus about what kind of leader the Messiah would be (military, priestly, political), there was a widespread anticipation of a redeemer and restorer of the people of Israel in the Messiah. However, the effect of the crucifixion on any of these pictures is illustrated well in Luke 24:18-21.

“Then one of them, named Cleopas, answered him, “Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?” And he said to them, “What things?” And they said to him, “Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, a man who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since these things happened.”

“Then one of them, named Cleopas, answered him, “Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?” And he said to them, “What things?” And they said to him, “Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, a man who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since these things happened.”

There are a few points worth bringing attention to here: Jesus was considered at least a mighty prophet (possibly not called the Messiah because of His recent crucifixion), these disciples “had hoped” (past tense) that He would redeem Israel, and it was the third day since Jesus was crucified. Whatever majesty His disciples ascribed to Him before, they did so no more with Him being dead. Whatever hopes they placed on Him, they forsook these following the crucifixion. Whatever thoughts they had about the future, they did not expect Jesus’ resurrection on the third day. Considering this outlook, it is inexplicable that Jesus’ disciples would somehow declare Jesus the risen Christ (Greek for Messiah) in the absence of some vindicating action on the part of Jesus.

Second, those who think it was commonplace to declare a would-be messiah to in fact be God’s Anointed One (Messiah), even after the death of such a messianic hopeful, should do a little more research. That dead messianic hopefuls were abandoned after death can even be found within the New Testament itself, concerning another Galilean, named Judas, for he was killed and his followers scattered (Acts 5:37). It is significant that there were many other false-messiahs who had significant followings, but no following after their death (Craig Keener, Bible Background Commentary NT, p.170-171, FF Bruce, New Testament History, p.338-339). NT Wright captures this point well when he states, “Anybody who knew anything about messiahs knew that a messiah who had been crucified by the pagans was a failed messiah, a sham.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.244). That the disciples would at such a point be inclined to start a new religion under a dead messiah is without historical precedent in Judaism, so what about the critic’s case that there might be parallels with pagan myths?

Second, those who think it was commonplace to declare a would-be messiah to in fact be God’s Anointed One (Messiah), even after the death of such a messianic hopeful, should do a little more research. That dead messianic hopefuls were abandoned after death can even be found within the New Testament itself, concerning another Galilean, named Judas, for he was killed and his followers scattered (Acts 5:37). It is significant that there were many other false-messiahs who had significant followings, but no following after their death (Craig Keener, Bible Background Commentary NT, p.170-171, FF Bruce, New Testament History, p.338-339). NT Wright captures this point well when he states, “Anybody who knew anything about messiahs knew that a messiah who had been crucified by the pagans was a failed messiah, a sham.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.244). That the disciples would at such a point be inclined to start a new religion under a dead messiah is without historical precedent in Judaism, so what about the critic’s case that there might be parallels with pagan myths?

Third, though there are parallels put forward between ancient Greco-Roman mystery religions and Christianity, the parallels are exaggerated and often misrepresented or distorted by the skeptics of Christianity. I will have more to say about this below, but at this point, I would like to state what some of these exaggerations and distortions are, in order to deal with them individually in due time. In Reinventing Jesus, J. Ed Komoszewski, M. James Sawyer, and Daniel B. Wallace expose five faulty assumptions behind alleged parallels between Christianity and pagan religions: the composite fallacy, the terminology fallacy, the dependency fallacy, the chronological fallacy, and the intentional fallacy. I will explain what each of these mean as I refer to the alleged parallels, starting with the chronological fallacy.  The proponent of the Christian borrowing theory, wherein Christianity borrows from pagan religions, must assume significant pagan influence on Christians in the beginning of this new religion. However, “What is often overlooked when one considers parallels and dependence is whether Palestinian Jews of the first century A.D. would have borrowed essential beliefs from pagan cults. Remember that the church was at first composed almost entirely of Jews.” (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.231). They go on to point out that there is so far no archaeological evidence of mystery religions in Palestine in the early part of the first century and that the first century Jews refused to blend their religion. Judaism, as with Christianity, was strictly monotheistic, whereas the pagan cults were polytheistic. Therefore, pagan influence in the Jewish context appears non-existent, and would thus not likely have any influence on the Jewish beginnings of Christianity either. At this time, also, the mystery religions were local cults and would not extend influence beyond their own borders. A couple hundred years later, pagan mystery religions started to compete with Christianity and had definite features that paralleled Christian concepts, but this is not the question. The question is what was happening in the very beginning of the Christian movement, and to this it must be stated clearly that the alleged parallels that surfaced much later were not existent. Thus, they cannot be used by the skeptic to explain the origin of the Christian faith. As I have shown above, even according to skeptical scholars, the Christians were proclaiming the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ within 3 years of the event. If any borrowing happened, it went the other way: mystery religions borrowing from Christianity (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.222-235, William Lane Craig, The Son Rises, p.127, in Jesus Under Fire, p.159).

The proponent of the Christian borrowing theory, wherein Christianity borrows from pagan religions, must assume significant pagan influence on Christians in the beginning of this new religion. However, “What is often overlooked when one considers parallels and dependence is whether Palestinian Jews of the first century A.D. would have borrowed essential beliefs from pagan cults. Remember that the church was at first composed almost entirely of Jews.” (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.231). They go on to point out that there is so far no archaeological evidence of mystery religions in Palestine in the early part of the first century and that the first century Jews refused to blend their religion. Judaism, as with Christianity, was strictly monotheistic, whereas the pagan cults were polytheistic. Therefore, pagan influence in the Jewish context appears non-existent, and would thus not likely have any influence on the Jewish beginnings of Christianity either. At this time, also, the mystery religions were local cults and would not extend influence beyond their own borders. A couple hundred years later, pagan mystery religions started to compete with Christianity and had definite features that paralleled Christian concepts, but this is not the question. The question is what was happening in the very beginning of the Christian movement, and to this it must be stated clearly that the alleged parallels that surfaced much later were not existent. Thus, they cannot be used by the skeptic to explain the origin of the Christian faith. As I have shown above, even according to skeptical scholars, the Christians were proclaiming the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ within 3 years of the event. If any borrowing happened, it went the other way: mystery religions borrowing from Christianity (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.222-235, William Lane Craig, The Son Rises, p.127, in Jesus Under Fire, p.159).

2. Another unique feature of the beginnings of Christianity is the concept of resurrection. I have mentioned this above, but here it deserves special attention. To the afore mentioned point about Jesus’ disciples not seeing what was expected of the Messiah as present in a crucified Jesus, I could add that even if they did still regard Jesus as the Messiah, it is still highly unlikely that they would expect His resurrection from the dead.  First, according to the Jewish understanding of resurrection (and remember, these are Jews in the early church) there would be a physical resurrection at the end of the world. This was an event that would take place at the end of the world and was not an event expected within history. Now, there were examples in the Old Testament and even Jesus’ ministry of people being raised from the dead, but these people would die again. In contrast, considering the Christian belief in the resurrection, of which Jesus is the firstfruits, the hope is not simply return to this life, but a new life altogether (1 Corinthians 15:19-23). Prior to the beginning of Christianity, there was simply no belief in what might be called a “pre-resurrection” or the Messiah being resurrected before everyone else. NT Wright pounds this point home as he surveys Jewish texts from biblical and extrabibilical sources.

First, according to the Jewish understanding of resurrection (and remember, these are Jews in the early church) there would be a physical resurrection at the end of the world. This was an event that would take place at the end of the world and was not an event expected within history. Now, there were examples in the Old Testament and even Jesus’ ministry of people being raised from the dead, but these people would die again. In contrast, considering the Christian belief in the resurrection, of which Jesus is the firstfruits, the hope is not simply return to this life, but a new life altogether (1 Corinthians 15:19-23). Prior to the beginning of Christianity, there was simply no belief in what might be called a “pre-resurrection” or the Messiah being resurrected before everyone else. NT Wright pounds this point home as he surveys Jewish texts from biblical and extrabibilical sources.

“No second-Temple Jewish texts speak of the Messiah being raised from the dead. Nobody would have thought of saying, ‘I believe that so-and-so really was the Messiah; therefore he must have been raised from the dead.’”

“The world of Judaism had generated, from its rich scriptural origins, a rich variety of beliefs about what happened, and would happen, to the dead. But it was quite unprepared for the new mutation that sprang up, like a totally unexpected plant, within the already well-stocked garden.”

“As we saw in reviewing the extensive second-Temple literature on resurrection, at no point did anyone envisage a Messiah who would die a shameful death, let alone be raised from the dead.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.25, 206, 243).

Wright goes on to remark that “it is striking that the story bears no sign of anyone saying, ‘Ah yes, we should have expected this.’ Just the opposite.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.628). The disciples’ portrayal as quite surprised and even in disbelief supports the historicity of the accounts. The resurrection of Jesus was an event that was totally unique, even within the Jewish picture of resurrection in general, so it must have required significant impetus.

Second, not only was there no expectation of a pre-resurrection event prior to the general resurrection at the end of the age, there was no belief that resurrection was something that would happen to just one person in history, even if that one person happened to be the Messiah. After describing the picture of resurrection given in the Gospels of Jesus in His resurrected state, Craig Blomberg adds, “Yet no pre-Christian Jew anticipated the resurrection of one person, even the Messiah, in advance of the general resurrection.” (The Historical Reliability of the Gospels, p.139).This may make it seem as though the Jewish concept of resurrection was abandoned by the Christians, but this is simply not the case. The Christians maintained their Jewish beliefs, being Jews, but added to this the revelation that the Christ actually was supposed to be crucified and resurrected in history, as NT Wright aptly describes.

Second, not only was there no expectation of a pre-resurrection event prior to the general resurrection at the end of the age, there was no belief that resurrection was something that would happen to just one person in history, even if that one person happened to be the Messiah. After describing the picture of resurrection given in the Gospels of Jesus in His resurrected state, Craig Blomberg adds, “Yet no pre-Christian Jew anticipated the resurrection of one person, even the Messiah, in advance of the general resurrection.” (The Historical Reliability of the Gospels, p.139).This may make it seem as though the Jewish concept of resurrection was abandoned by the Christians, but this is simply not the case. The Christians maintained their Jewish beliefs, being Jews, but added to this the revelation that the Christ actually was supposed to be crucified and resurrected in history, as NT Wright aptly describes.

“It is, then, remarkable that Christianity…never seems to have developed even the beginnings of a spectrum of belief, either of the pagan variety or of the Jewish variety, but always stuck to one point on the Jewish scale. It is more remarkable that from within this position it then developed, virtually across the board, new ways of speaking about what resurrection involved and how it would come about which could not have been predicted from the Jewish sources but which nevertheless give every appearance of remaining in strong continuity with them.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.552).

Christians still believed that there would be a general resurrection at the end of time, but contrary to prior belief, they were convinced both that a resurrection did happen before this and that it did happen to the Messiah. These two points strongly suggest that there was some extraordinary factor that led to this new understanding of resurrection and that this was what got the Christian movement going. This covers the Jewish side of things, but Wright also mentioned the pagan understanding, so what further comment could be made on that account?

Third, although a critic can make parallels with ancient pagan religions and Christianity look convincing, what they are not telling you is that they are using exclusively Christian terms to refer to elements in a mystery religion that do not deserve the designations. Komoszewski, Sawyer, and Wallace call this the terminology fallacy and it is a sneaky one. As Freke and Gandy put it, “Each mystery religion taught its own version of the myth of the dying and resurrecting Godman, who was known by different names in different places.” (Laughing Jesus, p.55). Faced with such a description, I always find Ronald Nash’s comment appropriate, for he observes that “one frequently encounters scholars who first use Christian terminology to describe pagan beliefs and practices and then marvel at the awesome parallels they think they have discovered.” (The Gospel and the Greeks, p.116). In other words, a comparison may sound very compelling until the actual pagan myth is examined in its own terms. In the interest of not simply trading assertions, I intend to look at what some supposed parallels actually look like.

Third, although a critic can make parallels with ancient pagan religions and Christianity look convincing, what they are not telling you is that they are using exclusively Christian terms to refer to elements in a mystery religion that do not deserve the designations. Komoszewski, Sawyer, and Wallace call this the terminology fallacy and it is a sneaky one. As Freke and Gandy put it, “Each mystery religion taught its own version of the myth of the dying and resurrecting Godman, who was known by different names in different places.” (Laughing Jesus, p.55). Faced with such a description, I always find Ronald Nash’s comment appropriate, for he observes that “one frequently encounters scholars who first use Christian terminology to describe pagan beliefs and practices and then marvel at the awesome parallels they think they have discovered.” (The Gospel and the Greeks, p.116). In other words, a comparison may sound very compelling until the actual pagan myth is examined in its own terms. In the interest of not simply trading assertions, I intend to look at what some supposed parallels actually look like.

Cybele and Attis

a. One commonly cited parallel of Jesus’ death and resurrection is the myth of Cybele and Attis, and though there are different forms of the myth, the core remains the same. The mother goddess Cybele loved Attis, a shepherd of Asia Minor, but he was unfaithful to her, so she drove him insane, resulting in Attis castrating himself and bleeding to death. Cybele’s grief brought death to the world, but when she returned Attis to life, life also returned to the earth. This corresponded to the plant cycle, with Attis death being connected to harvesting of crops. Sound vaguely like the story of Jesus? Well, vaguely, but there are still a few problems that cannot be ignored. Significantly, despite what the proponent might like to call the alleged “resurrection”, there is no account of it in the myth itself. Cybele can only preserve the body of Attis, keep his hair growing, and allow his little finger to move. If that is comparable to a resurrected Lord of glory, I would suggest looking up the definition of “resurrected” and “glory” in a dictionary. Furthermore, instead of this being a one-time event in history, as with Jesus’ resurrection, the Attis cycle happens every year and worshippers are focusing on a good crop, not attaining resurrection life through faith in the god’s resurrection. NT Wright makes this point well when he states, “when the Christians spoke of the resurrection of Jesus they did not suppose it was something that happened every year, with the sowing of seed and the harvesting of crops.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.81). In the case of the disciples, if they really were just referring to something like a cycle that had not happened as an event in history, it is hard to see why they would call it a resurrection, why it would be after 3 days, and why it would be on Sunday and not Saturday when the Jews had the Sabbath already in place. In addition, this theory is also guilty of the chronological fallacy, for even a relatively vague picture of a resurrection does not appear in this cult until the middle of the second century, at the earliest. Whatever elements similar to Christianity that the myth contains are best explained by dependence on the spread of the Christian faith in the Roman Empire, if any dependence exists at all. Whatever the case, it would certainly not be correct to suggest that this myth was the source for the beginnings of Christianity.

Adonis

b. Another cited parallel is with the Greek mythological figure, Adonis. Adonis was syncretistically identified with the Mesopotamian Tammuz later in the Tammuz myth’s development. According to Habermas and Licona, the Adonis myth is the first clear parallel of a dying and rising god, but I will begin with Tammuz. It has been claimed that Tammuz was raised by the goddess Ishtar, but this is pure conjecture, for the end of the myth is lost in the relevant texts. In fact, another text, “The Death of Dumuzi” (Sumerian for Tammuz) reveals Ishtar not rescuing Tammuz from the underworld. When Adonis was blended together with Tammuz, the early texts still indicate nothing of a resurrection. This theory also encounters the obstacle of chronology, for the first versions involving a resurrection of Adonis come from the middle of the second century, and is thus comparable to the Attis myth in that respect. Any comparison with Christianity, however, reveals no useful information regarding the origin of the Christian faith, but only possible influence of Christianity on the Adonis cult.

Osiris

c. Even though the previous two alleged parallels commit the chronological fallacy, there is one supposed parallel that actually does pre-date Christianity that has been put forward as a candidate for Christian borrowing. Osiris was an Egyptian deity that also came to be identified as the Greek god Dionysius. According to one version of the story, Osiris was killed by his brother, chopped up into fourteen pieces, and scattered throughout Egypt. The goddess Isis gathered the pieces and brought him back to life. Sound like Jesus’ resurrection? Again, vaguely, but also again, there are further hurdles the critic must jump in proving his case. Though Isis brought back to life what she collected, she was only able to find thirteen pieces. So, in some sense, not all of Osiris was resurrected, if resurrected is even the right word. I can say this because it is questionable whether he was actually brought back to life on earth or was seen by others, as Jesus certainly was. Furthermore, he was given the status of god of the underworld, suggesting that he was not resurrected to earthly life, but simply made to rule over the realm of the dead. Added to the uncertain nature of his coming back to life is the fact that there are other versions of the story that do not include any sort of coming back to life. In fact, many worshippers desired to be buried in the same ground that, according to tradition, Osiris’ body lay. Other accounts refer to Osiris simply as the sun. Considering the resurrection of Jesus, the early reports agree that He died, was buried, and was raised from the dead. Though the Osiris myth certainly comes before Christianity, it can hardly be even suggested that dependency on the myth is what got the Christian movement going. Doing so is to commit another pitfall described by Komoszewski, Sawyer, and Wallace; namely the dependency fallacy.  This occurs when interpreters believe that Christianity borrowed not only the form, but also the substance of the mystery religions. Even though I think the parallels to be largely exaggerated, the presence of parallels does not necessitate borrowing. It is perfectly legitimate to see the Christian movement as using language and forms of the day that would be understood, without requiring that they therefore made up the religion by following pagan myths. Also, it is important to point out that, even though there may be parallels that can be seen with Greek sources and the New Testament, the majority of these can better be explained by reference to the Old Testament and other Jewish literature. Gary Habermas emphasizes this idea and summarizes what can be seen, while having already pointed out other differences between Greek miracle accounts and the New Testament accounts (though he mentions Jesus’ miracles in general, he also discusses the resurrection in particular).

This occurs when interpreters believe that Christianity borrowed not only the form, but also the substance of the mystery religions. Even though I think the parallels to be largely exaggerated, the presence of parallels does not necessitate borrowing. It is perfectly legitimate to see the Christian movement as using language and forms of the day that would be understood, without requiring that they therefore made up the religion by following pagan myths. Also, it is important to point out that, even though there may be parallels that can be seen with Greek sources and the New Testament, the majority of these can better be explained by reference to the Old Testament and other Jewish literature. Gary Habermas emphasizes this idea and summarizes what can be seen, while having already pointed out other differences between Greek miracle accounts and the New Testament accounts (though he mentions Jesus’ miracles in general, he also discusses the resurrection in particular).

“We must conclude, therefore, that the Evangelists’ records of the miracles of Jesus cannot be explained by influence from the Hellenistic stories. The lack of clarity in the concept of the divine man, the areas of divergence from the Gospels, the Old Testament and Jewish parallels to the Gospels, the very absence of clear, pre-Christian Hellenistic accounts, and the inability to explain the most crucial components of the Christian gospel all seriously militate against the thesis.” (In Jesus Under Fire, p.122).

d. Even if there were widely acknowledged and evidentially supported parallels between Christianity and earlier pagan myths, there would still be other reasons to consider the Christian account to be of an entirely different kind. More will be shown in the final two points, but suffice it to say here that what people thought of the myths and what people thought of the stories of Jesus was entirely different. There is a common picture of the ancient world that suggests that it would believe anything, whereas our modern society is considered to be more grounded in what can be proven by scientific means. This may be true in general, but it is worth pointing out what some thought of the myths in the ancient world. Craig Keener illustrates this well in quoting David Bentley Hart. “One philosopher warns about our tendency to deplore earlier cultures’ uncritical embrace of the assumptions of their age while congratulating ‘our own largely uncritical obedience to the common basic assumptions of our own.’” (Miracles, p.102).

Plutarch

That being said, there were those in the ancient world who had views almost analogous to modern critical scholars. It was the historian Plutarch that mentioned the devotion of those who wanted to be buried in the same plot of ground as Osiris, but interestingly, he also cautions his readers in regard to the myths.

“Whenever you hear the traditional tales which the Egyptians tell about the gods, their wanderings, their dismemberments, and many experiences of the sort,…you must not think that any of these tales actually happened in the manner in which they are related.” (Quoted in Reinventing Jesus, p.252).

Arrian, in his biography of Alexander the Great, complained that some writers tell of wonders at the ends of the earth only because they can get away with inventing stories that their readers cannot check. Diodorus Siculus even attempted to “demythologize” some accounts, depicting how he saw accounts reworked into mythological ones. Thucydides claimed to deal with probable events, rather than the pleasant-sounding myths. Livy warns that the more incredible reports are believed, the more others will spring up (Craig Keener, Miracles, p.90-92). Christianity, on the other hand, is of a different kind. Craig Blomberg compares the difference in the concepts of Jesus’ resurrection and the pagan myths as follows, “None of the ancient myths and stories of dying and rising gods refers to real human individuals known to have lived among the very people narrating the stories within their living memory. Instead, they are closely tied to the annual death and birth of seasonal vegetation.” (The Historical Reliability of the Gospels, p.138-139). Jesus was a living human being, verified by Christian and non-Christian sources. The kind of story given in the Gospels, though labeled mythical by some, is just not that kind of story. A greater writer and reader of myths, CS Lewis, made this point well when he commented,

“All I am in private life is a literary critic and historian, that’s my job. And I’m prepared to say on that basis if anyone thinks the Gospels are either legends or novels, then that person is simply showing his incompetence as a literary critic. I’ve read a great many novels and I know a fair amount about the legends that grew up among early people, and I know perfectly well the Gospels are not that kind of stuff.” (Christian Reflections, p.209).

Furthermore, whatever people in the ancient world thought about the myths, it was certainly not a historical depiction based on eyewitness account in the way that Jesus is described in the New Testament. It was not as much a literal description of reality as it was a metaphorical description of nature. NT Wright is worth quoting at length to bring a fitting end to the suggestion that the beliefs of Christianity were not a new thing as far as the religions of the ancient Roman Empire were concerned.

“Did any worshipper in these cults, from Egypt to Norway, at any time in antiquity, think that actual human beings, having died, actually came back to life? Of course not. These multifarious and sophisticated cults enacted the god’s death and resurrection as a metaphor, whose concrete referent was the cycle of seed-time and harvest, of human reproduction and fertility. Sometimes, as in Egypt, the myths and rituals included funeral practices: the aspiration of the dead was to become united with Osiris. But the new life they might thereby experience was not a return to the life of the present world. Nobody actually expected the mummies to get up, walk about and resume normal living; nobody in that world would have wanted such a thing, either. That which Homer and others meant by resurrection was not affirmed by the devotees of Osiris or their cousins elsewhere.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.80-81).

“Did any worshipper in these cults, from Egypt to Norway, at any time in antiquity, think that actual human beings, having died, actually came back to life? Of course not. These multifarious and sophisticated cults enacted the god’s death and resurrection as a metaphor, whose concrete referent was the cycle of seed-time and harvest, of human reproduction and fertility. Sometimes, as in Egypt, the myths and rituals included funeral practices: the aspiration of the dead was to become united with Osiris. But the new life they might thereby experience was not a return to the life of the present world. Nobody actually expected the mummies to get up, walk about and resume normal living; nobody in that world would have wanted such a thing, either. That which Homer and others meant by resurrection was not affirmed by the devotees of Osiris or their cousins elsewhere.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.80-81).

(J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.224-231, 250-255, Gary Habermas and Michael Licona, The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus, p.90-92, William Lane Craig, The Son Rises, p.129-134, in Jesus Under Fire, p.161).

3. The two points above about the disciples likely not continuing to consider a crucified Jesus as the Messiah, and at any rate, not expecting His resurrection, are strong points to consider. However, they equally apply, and are in fact multiplied, when we consider the case of the Apostle Paul. While the disciples were at least followers of Jesus during His earthly life and ministry, and would be sympathetic to at least the idea of Jesus being the Messiah, Paul had no such background or inclination. In any discussion of the origin of the Christian faith, the conversion of Paul must be considered.  First, Paul was not in a position to be sympathetic to Jesus’ cause, and in fact, persecuted the Christians, as discussed above. He would not be saddened by the apparent failure of Jesus as Messiah, because as far as Paul was concerned, Jesus was a blasphemer, and the very fact that Jesus was on the cross meant that He was cursed by God (Galatians 3:14) and obviously not the Messiah. Or so it seemed for a time. Of course, the fact that I am quoting from the letter of Galatians in the Christian canon shows that Paul changed his mind about the significance of Jesus being hanged on a cross, but the question remains: what made him change his mind? Well, as I explained above, the explanation given by Paul himself in his letters and by Luke in Acts was that he had seen the risen Jesus. This is the only explanation of earliest Christianity, so it stands to reason that this would actually be an accurate way to describe the origin of the Christian faith, in conjunction with the other apostles appeared to previously of course. It also makes sense in light of Paul’s previous life, for it would take quite a significant catalyst to change Paul from being a persecutor of the church to one of its most zealous proponents, if not the most. This is part of the reason why the conversion of Paul and his experience of Jesus is so widely accepted on historical grounds. At the same time it is both extremely difficult to deny and extremely difficult to explain, in the absence of a life-changing event. Josh McDowell describes the attempt of Oxford professors Gilbert West and Lord Lyttleton to destroy the basis of the Christian faith. In their investigation of the events surrounding the resurrection of Jesus (including Paul’s conversion in particular), however, they came to the conclusion that the evidence was sound and they became Christians. McDowell quotes Lyttleton as having written, “The conversion and apostleship of Saint Paul alone, duly considered, was of itself a demonstration sufficient to prove Christianity to be a Divine Revelation.” (More Than A Carpenter, p.87).

First, Paul was not in a position to be sympathetic to Jesus’ cause, and in fact, persecuted the Christians, as discussed above. He would not be saddened by the apparent failure of Jesus as Messiah, because as far as Paul was concerned, Jesus was a blasphemer, and the very fact that Jesus was on the cross meant that He was cursed by God (Galatians 3:14) and obviously not the Messiah. Or so it seemed for a time. Of course, the fact that I am quoting from the letter of Galatians in the Christian canon shows that Paul changed his mind about the significance of Jesus being hanged on a cross, but the question remains: what made him change his mind? Well, as I explained above, the explanation given by Paul himself in his letters and by Luke in Acts was that he had seen the risen Jesus. This is the only explanation of earliest Christianity, so it stands to reason that this would actually be an accurate way to describe the origin of the Christian faith, in conjunction with the other apostles appeared to previously of course. It also makes sense in light of Paul’s previous life, for it would take quite a significant catalyst to change Paul from being a persecutor of the church to one of its most zealous proponents, if not the most. This is part of the reason why the conversion of Paul and his experience of Jesus is so widely accepted on historical grounds. At the same time it is both extremely difficult to deny and extremely difficult to explain, in the absence of a life-changing event. Josh McDowell describes the attempt of Oxford professors Gilbert West and Lord Lyttleton to destroy the basis of the Christian faith. In their investigation of the events surrounding the resurrection of Jesus (including Paul’s conversion in particular), however, they came to the conclusion that the evidence was sound and they became Christians. McDowell quotes Lyttleton as having written, “The conversion and apostleship of Saint Paul alone, duly considered, was of itself a demonstration sufficient to prove Christianity to be a Divine Revelation.” (More Than A Carpenter, p.87).

Second, it is also significant to consider what Paul was converted from; namely, Pharisaic Judaism. According to this strict party, to use Paul’s own words (Acts 26:5), there was strong belief in the resurrection of the dead. However, as Acts 24:14-15 tells us, again in Paul’s own words, though Paul continued to believe in the resurrection of the just and the unjust, the Jews still considered Christianity a sect. It is hard to understand why Paul would separate himself from his kinsmen, whom he clearly longed for (Romans 10:1), if there was nothing significant that led him to proclaim that Jesus had been resurrected prior to the general resurrection at the end of the age. Again, why would he believe in the resurrection of just one person, even the Messiah, when there was no such belief before Jesus came along? This all seems quite inexplicable in the absence of a monumental event, but perhaps there is some naturalistic hypothesis that could offer such a catalyst in Paul’s case.

Second, it is also significant to consider what Paul was converted from; namely, Pharisaic Judaism. According to this strict party, to use Paul’s own words (Acts 26:5), there was strong belief in the resurrection of the dead. However, as Acts 24:14-15 tells us, again in Paul’s own words, though Paul continued to believe in the resurrection of the just and the unjust, the Jews still considered Christianity a sect. It is hard to understand why Paul would separate himself from his kinsmen, whom he clearly longed for (Romans 10:1), if there was nothing significant that led him to proclaim that Jesus had been resurrected prior to the general resurrection at the end of the age. Again, why would he believe in the resurrection of just one person, even the Messiah, when there was no such belief before Jesus came along? This all seems quite inexplicable in the absence of a monumental event, but perhaps there is some naturalistic hypothesis that could offer such a catalyst in Paul’s case.

Third, the skeptic’s theory most likely seeks to treat Paul’s conversion as nothing out of the ordinary. After all, people convert from one religion to another all the time and this does not prove the truth or transforming power of any particular religion, right? Well, even though that may be true, it is not just any old conversion story when we consider what happened with Paul. Mike Licona sums this up well.

“People usually convert to a particular religion because they have heard the message of that religion from a secondary source and believed the message. Paul’s conversion was based on what he perceived to be a personal appearance of the risen Jesus.” (The Resurrection of Jesus, p.440).

Unlike most who convert from one religion to another, Paul was in a position to really evaluate what the truth was and act upon it. As strong as I think this point is, how would the borrowing theory fare if I consider yet another “even if” scenario, for the sake of argument? Well, the idea that Christianity, in its very beginnings, simply borrowed ideas from pagan religions assumes that there would be a story, analogous to the Christian story that formed, available for borrowing. However, in making this assumption, yet another fallacy is committed, which Komoszewski, Sawyer, and Wallace call the composite fallacy.  The critic of Christianity assumes that pagan religions can just be lumped all together as though they were one religion; one that is virtually identical to Christianity in many of its essential features. I submit that this must be assumed, since there is very little spectrum of belief in early Christianity, as mentioned above. The picture offered to the disciples and Paul would have to be a unified picture from the mystery religion of the pagans. However, there are again problems with this idea, the most significant of which is that no such unified mystery religion existed! Albert Schweitzer brought attention to this at the beginning of the 20th century.

The critic of Christianity assumes that pagan religions can just be lumped all together as though they were one religion; one that is virtually identical to Christianity in many of its essential features. I submit that this must be assumed, since there is very little spectrum of belief in early Christianity, as mentioned above. The picture offered to the disciples and Paul would have to be a unified picture from the mystery religion of the pagans. However, there are again problems with this idea, the most significant of which is that no such unified mystery religion existed! Albert Schweitzer brought attention to this at the beginning of the 20th century.

“Almost all popular writings fall into this kind of inaccuracy. They manufacture out of the various fragments of information a kind of universal Mystery-religion which never actually existed, least of all in Paul’s day.” (Paul and His Interpreters, p.192).

It could further be pointed out that there was variation within the same mystery religion in different places and at different times, so any suggestion of a unification of all mystery religions to feed the relevant elements into Christianity is a myth in itself. Putting all that aside, though, would such alleged borrowing of religion be enough to convince an extremely zealous Pharisee to abandon his cherished Jewish beliefs and become a follower and proclaimer of Jesus, the god-man who dies and rises again? I do not see how it could. The idea that Paul was suddenly changed from following his Jewish roots, obedient to the law of Moses, in order to convert to a form of religion that every other religion at the time was offering makes little to no sense, leaning more toward the nonsense side of things. According to this understanding, Paul could have just as easily become a worshipper of Osiris, forsaking belief in the one true God for polytheistic superstition. No, the radical transformation of Paul’s life requires a radically transforming event, one that would cause him to rethink his views about the Messiah. It is this kind of transformation among the followers of Jesus that is the subject of the last point of this section (J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.223-224, Michael Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus, p.373-440, Gary Habermas and Michael Licona, The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus, p.64-65).

4. Frank Morison was another person who set out to disprove the resurrection, but also found himself overwhelmed by evidence and accepted that the resurrection of Jesus actually happened. In his book on the resurrection, he points out various extraordinary happenings in respect to the disciples after they were originally afraid prior to the reported meetings with the risen Jesus.

“The terrors and the persecutions which these men ultimately had to face and did face unflinchingly, do not admit of a half-hearted adhesion secretly honeycombed with doubt. The belief has to be unconditional and of adamantine strength to satisfy the conditions. Sooner or later, too, if the belief was to spread it had to bite its way into the corporate consciousness by convincing argument and attempted proof.

“The terrors and the persecutions which these men ultimately had to face and did face unflinchingly, do not admit of a half-hearted adhesion secretly honeycombed with doubt. The belief has to be unconditional and of adamantine strength to satisfy the conditions. Sooner or later, too, if the belief was to spread it had to bite its way into the corporate consciousness by convincing argument and attempted proof.

Now the peculiar thing about this phenomenon is that, not only did it spread to every single member of the Party of Jesus of whom we have any trace, but they brought it to Jerusalem and carried it with inconceivable audacity into the most keenly intellectual centre of Judea, against the ablest dialecticians of the day, and in the face of every impediment which a brilliant and highly organized camarilla could devise. And they won. Within twenty years the claim of these Galilean peasants had disrupted the Jewish Church and impresses itself upon every town on the Eastern littoral of the Mediterranean from Caesarea to Troas. In less than fifty years it had begun to threaten the peace of the Roman Empire.

When we have said everything which can be said about the willingness of certain types of people to believe what they want to believe, to be carried away by their emotions, and to assert as fact what has originally reached them as hearsay, we stand confronted with the greatest mystery of all. Why did it win?” (Who Moved the Stone?, p.127).

It really is overwhelming to think of the transformation that occurred in the disciples, especially when their state before the appearances is considered, as explained above. The disciples would have been lost in confusion and despair, but then all of a sudden, they are proclaiming Jesus’ resurrection in Jerusalem, the very city where He was crucified and buried. Something had definitely changed in them, so much so that they made a significant impact on people in Jerusalem, Judea, and even Rome itself (Acts).  First, to start with Jerusalem, not only did they have a different outlook on the Messiah and His resurrection, but they were also almost asking to be persecuted by proclaiming the message right where Jesus had been arrested and executed for basically the same message. It needs to be understood that it is not simply the fact that the disciples are different because of their belief, because many others have been changed by various beliefs, yet this does not prove anything. The important part to see in the case of the disciples is the specific situation that they were in. Jesus’ disciples were in a potentially dangerous situation, even before they started proclaiming the resurrection, for they were associated with a rebel who had just been arrested and executed. However, after they started proclaiming the resurrection, the antagonism of the Jewish leaders toward them was aggravated. They were threatened and beaten, but continued to proclaim Jesus and the resurrection (Acts 4-5). It could be said that they brought this trouble on themselves, when considering the fact that, since they were Jews, they could have avoided persecution by just forgetting all this Jesus business and enjoy the rest of their lives in peace. There is no hint that this was a thought they were entertaining, but quite the contrary, Peter and John responded to the threats by answering, “Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge, for we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard.” (Acts 4:19-20). In some sense, the disciples were compelled to proclaim this message, so it was truly revolutionary and unparalleled in the eyes of Jesus’ followers.

First, to start with Jerusalem, not only did they have a different outlook on the Messiah and His resurrection, but they were also almost asking to be persecuted by proclaiming the message right where Jesus had been arrested and executed for basically the same message. It needs to be understood that it is not simply the fact that the disciples are different because of their belief, because many others have been changed by various beliefs, yet this does not prove anything. The important part to see in the case of the disciples is the specific situation that they were in. Jesus’ disciples were in a potentially dangerous situation, even before they started proclaiming the resurrection, for they were associated with a rebel who had just been arrested and executed. However, after they started proclaiming the resurrection, the antagonism of the Jewish leaders toward them was aggravated. They were threatened and beaten, but continued to proclaim Jesus and the resurrection (Acts 4-5). It could be said that they brought this trouble on themselves, when considering the fact that, since they were Jews, they could have avoided persecution by just forgetting all this Jesus business and enjoy the rest of their lives in peace. There is no hint that this was a thought they were entertaining, but quite the contrary, Peter and John responded to the threats by answering, “Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge, for we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard.” (Acts 4:19-20). In some sense, the disciples were compelled to proclaim this message, so it was truly revolutionary and unparalleled in the eyes of Jesus’ followers.

Second, considering the wider effects on the Roman Empire, the Christians were those who had “turned the world upside down” (Acts 17:6). Although they did not receive persecution exclusively for the same reasons among the pagans as they did among the Jews, they were persecuted nonetheless (Acts 14:22, 16:21-24; Philippians 1:27-30; 2 Timothy 3:12). In spite of this, the Christian faith was still spreading rapidly. It is interesting that one of the earliest non-Christian sources about Christianity, Pliny the Younger, reports that in his persecution of Christians, he found that true believers could not be forced to worship the gods or the emperor (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.200). So it is clear that the disciples of Jesus were committed to the gospel message and that no persecution could silence them, and thus, the Christian faith spread rapidly through the Roman Empire. The question is, then, could this be accounted for in terms of parallels with other religions?

Second, considering the wider effects on the Roman Empire, the Christians were those who had “turned the world upside down” (Acts 17:6). Although they did not receive persecution exclusively for the same reasons among the pagans as they did among the Jews, they were persecuted nonetheless (Acts 14:22, 16:21-24; Philippians 1:27-30; 2 Timothy 3:12). In spite of this, the Christian faith was still spreading rapidly. It is interesting that one of the earliest non-Christian sources about Christianity, Pliny the Younger, reports that in his persecution of Christians, he found that true believers could not be forced to worship the gods or the emperor (Gary Habermas, The Historical Jesus, p.200). So it is clear that the disciples of Jesus were committed to the gospel message and that no persecution could silence them, and thus, the Christian faith spread rapidly through the Roman Empire. The question is, then, could this be accounted for in terms of parallels with other religions?

Third, while the proposition that Christianity spread rapidly because it was made up of beliefs already widely held might initially sound plausible, it must maintain that status in looking through the specifics of the spread of Christianity. An important feature of a religious movement that is often overlooked or misinterpreted by skeptics is its main purpose or intention. Komoszewski, Sawyer, and Wallace refer to this as the intentional fallacy.  According to almost all mystery religions, history is cyclical, linked to the harvest cycle mentioned above. Christianity sees history as linear, going somewhere. So, on the one hand, you have the mystery religion, in which history is going nowhere, and on the other hand, you have Christianity, in which there is a purpose to history that God is accomplishing. Moving on to the question of persecution discussed in the previous points, this changes the perspective of how much the borrowing theory can really explain about the beginnings of Christianity. The pagans, who came to dominate the numbers of people being added to the church after the initial Jewish phase, were allowed to add gods to those that they already worshipped. However, in the case of Christianity, to become a Christian was to forsake all the other gods (Acts 14:15; 1 Thessalonians 1:9). In fact, this was at least part of the reason for persecution of Christians, because they forsook all the other gods. They were even called the “haters of the human race” and were disliked by all for their anti-social attitude, for Roman life was full of what Christians regarded as immorality and idolatry (FF Bruce, New Testament History, p.399-402, 410). If Christianity was really just a new mystery cult, it is hard to see why they would be persecuted as they were. Additionally, it is hard to see why anyone would be converted to Christianity, if all that Christians were offering was what was already offered by the local gods. Not only would Christianity apparently not add anything, but it could lead to new converts being persecuted. So the fact that Christianity continued to spread in spite of persecution shows that it did have something different to offer. It offered a hope that none of the mystery religions did, for it looked to the future vindication of God, instead of the present cycles. If you have a cyclical view of life, it makes sense to avoid persecution and to entreat as many gods as you see fit for crops, children, etc. However, if history is linear, with the resurrection of all people in view, promised and guaranteed by the resurrection of Jesus, Christians could hope for resurrection life. They could look into the face of their persecutors with boldness, even proclaiming the gospel to them. This was no rehashed religion with a fresh face, but something the world had never seen before. NT Wright sums this point up well when he states,

According to almost all mystery religions, history is cyclical, linked to the harvest cycle mentioned above. Christianity sees history as linear, going somewhere. So, on the one hand, you have the mystery religion, in which history is going nowhere, and on the other hand, you have Christianity, in which there is a purpose to history that God is accomplishing. Moving on to the question of persecution discussed in the previous points, this changes the perspective of how much the borrowing theory can really explain about the beginnings of Christianity. The pagans, who came to dominate the numbers of people being added to the church after the initial Jewish phase, were allowed to add gods to those that they already worshipped. However, in the case of Christianity, to become a Christian was to forsake all the other gods (Acts 14:15; 1 Thessalonians 1:9). In fact, this was at least part of the reason for persecution of Christians, because they forsook all the other gods. They were even called the “haters of the human race” and were disliked by all for their anti-social attitude, for Roman life was full of what Christians regarded as immorality and idolatry (FF Bruce, New Testament History, p.399-402, 410). If Christianity was really just a new mystery cult, it is hard to see why they would be persecuted as they were. Additionally, it is hard to see why anyone would be converted to Christianity, if all that Christians were offering was what was already offered by the local gods. Not only would Christianity apparently not add anything, but it could lead to new converts being persecuted. So the fact that Christianity continued to spread in spite of persecution shows that it did have something different to offer. It offered a hope that none of the mystery religions did, for it looked to the future vindication of God, instead of the present cycles. If you have a cyclical view of life, it makes sense to avoid persecution and to entreat as many gods as you see fit for crops, children, etc. However, if history is linear, with the resurrection of all people in view, promised and guaranteed by the resurrection of Jesus, Christians could hope for resurrection life. They could look into the face of their persecutors with boldness, even proclaiming the gospel to them. This was no rehashed religion with a fresh face, but something the world had never seen before. NT Wright sums this point up well when he states,

“Never before had there been a movement which began as a quasi-messianic group within Judaism and was transformed into the sort of movement which Christianity quickly became. Nor has any similar phenomenon ever occurred again. (The common post-Enlightenment perception of Christianity as simply ‘a religion’ masks the huge differences, at the point of origin, between this movement and, say, the rise of Islam or of Buddhism.) Both pagan and Jewish observers of this new movement found it highly anomalous: it was not like a club, not even like a religion (no sacrifices, no images, no oracles, no garlanded priests), certainly not like a racially based cult.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.17-18).

(J. Ed Komoszewski et al, Reinventing Jesus, p.234-235, Gary Habermas and Michael Licona, The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus, p.56-62).

It is clear that whatever got Christianity started had to be something very special and the same could be said concerning what kept it going through persecution. It is significant to consider the circumstances that Christianity arose in, since prior Jewish beliefs could not describe what the early Christians believed in, so there must have been something extraordinary to convince them of the resurrection of the Messiah. It is also significant that a popular naturalistic explanation utterly fails to explain the origin of the Christian faith, both in its inability to establish clear parallels, and in its inability to explain the commitment and transformation of the early disciples. The origin of the Christian faith is very unique indeed. It originates in a religion (Judaism) in which part of its belief in the resurrection was unanticipated and it grew rapidly in a culture (Paganism) that denied the possibility of resurrection altogether. Quotes from NT Wright and CFD Moule should sum this up well.

It is clear that whatever got Christianity started had to be something very special and the same could be said concerning what kept it going through persecution. It is significant to consider the circumstances that Christianity arose in, since prior Jewish beliefs could not describe what the early Christians believed in, so there must have been something extraordinary to convince them of the resurrection of the Messiah. It is also significant that a popular naturalistic explanation utterly fails to explain the origin of the Christian faith, both in its inability to establish clear parallels, and in its inability to explain the commitment and transformation of the early disciples. The origin of the Christian faith is very unique indeed. It originates in a religion (Judaism) in which part of its belief in the resurrection was unanticipated and it grew rapidly in a culture (Paganism) that denied the possibility of resurrection altogether. Quotes from NT Wright and CFD Moule should sum this up well.

“Even if we suppose the very unlikely hypothesis that the early disciples, all of them of course Jewish monotheists, had come to be convinced of Jesus’ divinity without any bodily resurrection having taken place, there is no reason to suppose that they would then have begun to think or talk about resurrection itself. If, somehow, they had come to believe that a person like Jesus had been exalted to heaven, that would be quite enough; why add extraneous ideas? What, from the point of view we are hypothesizing, could resurrection have added to exaltation or even divinization? Why would anyone work back by that route, to end up predicating something which nobody was expecting and which everybody knew had not happened.” (Resurrection of the Son of God, p.574).

“If the coming into existence of the Nazarenes, a phenomenon undeniably attested by the New Testament, rips a great hole in history, a hole of the size and shape of the Resurrection, what does the secular historian propose to stop it up with?…the birth and rapid rise of the Christian Church…remain an unsolved enigma for any historian who refuses to take seriously the only explanation offered by the Church itself.” (Quoted in The Son Rises, p. 131).

Click here to see part 5 of the article